IV. BAYREUTH AFTER RICHARD WAGNER:

IV. BAYREUTH AFTER RICHARD WAGNER:

WHAT FUTURE?

1 – Cosima’s Bayreuth, guardian of the Temple

When the composer died in 1883, the Bayreuth Festival management team felt like it was evolving in a kingdom that had suddenly lost its sovereign.

He, who built the temple by the strength of his will, was no more. He was survived by his family, his friends, his admirers who wanted the torch to continue to shine. But they did not all have the same idea how it should shine. They felt disoriented, abandoned, not knowing who to devote themselves to anymore… To whom to obey?

On her return from Venice to Bayreuth with their son Siegfried to accompany her husband’s remains, after the (grandiose) funeral, Cosima was prostrate in a deep retreat away from prying eyes and shut herself away in Villa Wahnfried for many months.

On her return from Venice to Bayreuth with their son Siegfried to accompany her husband’s remains, after the (grandiose) funeral, Cosima was prostrate in a deep retreat away from prying eyes and shut herself away in Villa Wahnfried for many months.

And yet! Despite a probable depression – according to testimonies – and gradually giving up her retreat, Wagner’s widow wanted to respect the will of the deceased to organize a new Festival in 1883. The rehearsals for Parsifal thus took place. And, hidden in the shadow of the boxes, Cosima gave her instructions, scrupulously drawn from the indications left by the composer.

The attachment to her husband’s work, close to veneration, was obvious in all aspects of Cosima‘s work. To the question: “What should one do with Wagner’s work?” in both literal and figurative sense, Cosima responded with a literal loyalty from this second Festival. Twelve performances were given like Wagner wanted them, at least on paper. The same for the following year, by the way, in 1884. Then began for Bayreuth a form of celebration of the work of the composer… with an unfailing loyalty! At the artistic helm of the Festival, Hermann Levi (the one who had been chosen by Wagner himself continued despite Cosima‘s prejudice to celebrate Holy Mass); at the financial helm, Adolf von Gross, the banker who managed the interests of the family.

The attachment to her husband’s work, close to veneration, was obvious in all aspects of Cosima‘s work. To the question: “What should one do with Wagner’s work?” in both literal and figurative sense, Cosima responded with a literal loyalty from this second Festival. Twelve performances were given like Wagner wanted them, at least on paper. The same for the following year, by the way, in 1884. Then began for Bayreuth a form of celebration of the work of the composer… with an unfailing loyalty! At the artistic helm of the Festival, Hermann Levi (the one who had been chosen by Wagner himself continued despite Cosima‘s prejudice to celebrate Holy Mass); at the financial helm, Adolf von Gross, the banker who managed the interests of the family.

But if it could seem legitimate after the fact for the widow of the Master to take over the heavy responsibility of running the Festival, the person who assisted Wagner for so many years, this legitimacy has not always been obvious. Cosima was met with opposition from the faithful “Guardians of the Temple”. Violent verbal and literary sparring matches took place within the precincts of Wahnfried and the Festspielhaus to know who should inherit the reins of the Festival. To entrust the responsibility of perpetuating the cult of Wagner to a woman? And more importantly, a foreigner? And whose musical qualities some, in addition, called into question? Siegfried Wagner recalled himself in his Memories the opposition his mother was met with from the “super-Wagnerians” as he himself called them: “In the eyes of these fanatics, my mother did not appear sufficiently “teutonic”! “

During the two Festivals that followed Wagner’s death, Cosima was personally involved in the celebration of the quasi-religious cult devoted to the composer. And the legitimacy of the composer’s widow imposed itself with force. Her extreme loyalty to the work convinced the most doubtful purists, more attached than even herself to perpetuating the holy work.

And she set up the project that Wagner himself had indicated in a letter to King Ludwig II of Bavaria as early as 1865, and which came off like a will: “My program to execute with the will and the help of my dear king. May and June 1865, Tristan and Isolde (…), May and June 1866, the entirety of Tannhäuser and Lohengrin, reworked and perfectly performed. (…) Resumption of Tristan. August 1867, The Ring of the Nibelung. In the newly built Theatre. August 1868, The Ring of the Nibelung. Resumption. August 1869 etc. “

That is how the Festival exclusively dedicated to Wagner’s work – part of the work in fact – took form. Since, because a composer was lacking the work was not “reworked”, it froze. Wagner was no longer there to perfect his work, to give it new versions, to adapt new ideas. From now on, Cosima‘s vigilance for the musical dramas of the Master to be “perfectly performed” made up for the lack of creation! “The artwork of the Future” little by little became in this mausoleum that of the past.

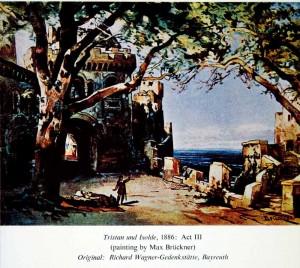

But, in 1886, faithful to the indications expressed by the Master, it was Tristan and Isolde that completed the program, followed by The Master-Singers in 1888, then Tannhäuser in 1891, and Lohengrin in 1894.

But, in 1886, faithful to the indications expressed by the Master, it was Tristan and Isolde that completed the program, followed by The Master-Singers in 1888, then Tannhäuser in 1891, and Lohengrin in 1894.

Finally, in 1896, a new production of The Ring. If the Festspielhaus had not benefited from the exclusive performance rights of Parsifal, if Cosima had not wanted to honor the works of her late husband, the Bayreuth festival would not have such a special place today in the musical universe…

Cosima was thus in charge and decided on the orientation of the Festival. She was also at the artistic helm and managed the staging of each of the works. As Wagner used to do, she showed on stage what she wanted to obtain. With more or less happiness, and as much success. Because if the spirit of the master was present in the organization, it was no longer there in the artistic “renewal“.

If the public was present to attend the performances of The Ring or The Master-Singers, it was much less so for Tristan and Isolde… which was given before an audience of barely two hundred spectators. On the other hand, Parsifal, which could only be applauded (if one can say that) on the Green Hill, of course played to a full house every time. The exclusivity prohibiting any performance of the work outside the precincts of the Festival, this “artistic exception” particularly favorable to the organization of the Festival, was defeated in the early 20th century by the New York Metropolitan Opera. Indeed, if the authorities of Bayreuth permitted performances in the form of concerts of Parsifal (in London in 1884, in New York in 1886, in Amsterdam in 1894), there had never been a full version or stage performance.

If the public was present to attend the performances of The Ring or The Master-Singers, it was much less so for Tristan and Isolde… which was given before an audience of barely two hundred spectators. On the other hand, Parsifal, which could only be applauded (if one can say that) on the Green Hill, of course played to a full house every time. The exclusivity prohibiting any performance of the work outside the precincts of the Festival, this “artistic exception” particularly favorable to the organization of the Festival, was defeated in the early 20th century by the New York Metropolitan Opera. Indeed, if the authorities of Bayreuth permitted performances in the form of concerts of Parsifal (in London in 1884, in New York in 1886, in Amsterdam in 1894), there had never been a full version or stage performance.

A dramatic turn of events erupted: thanks to a court ruling, the American Opera Houses were allowed to perform the ultimate masterpiece by Wagner, and on 24 December, 1903, the New York Metropolitan Opera staged the work, with many singers trained in Bayreuth on stage. Furious, Cosima forbade the singers who had betrayed by performing in New York to be invited again to Bayreuth. However, in Europe, Bayreuth’s monopoly over Parsifal continued until 1 January, 1914; on 31 December at midnight, several theaters began their performances. But in reality, shows that were not allowed were already staged in Amsterdam in 1905, 1906 and 1908.

A dramatic turn of events erupted: thanks to a court ruling, the American Opera Houses were allowed to perform the ultimate masterpiece by Wagner, and on 24 December, 1903, the New York Metropolitan Opera staged the work, with many singers trained in Bayreuth on stage. Furious, Cosima forbade the singers who had betrayed by performing in New York to be invited again to Bayreuth. However, in Europe, Bayreuth’s monopoly over Parsifal continued until 1 January, 1914; on 31 December at midnight, several theaters began their performances. But in reality, shows that were not allowed were already staged in Amsterdam in 1905, 1906 and 1908.

For the record, the first authorized performance was staged at the Liceu Theatre in Barcelona: it started at 10:30 pm, one hour and a half before midnight on 31 December, 1913, taking advantage of the one-hour time difference that existed at the time between Barcelona and Bayreuth.

2) Siegfried Wagner’s Bayreuth,

purveyor in spite of himself

On 9 September, 1906, Cosima suffered a severe heart attack that forced her to withdraw from the direction of the Festival: the old lady of Bayreuth was seventy years old. All eyes then turned to the one who, by his lineage, was widely expected to take over the reins of the Festival: the only male heir to the family, Siegfried Wagner.

The young man who had been affectionately nicknamed Fidi was then thirty-seven. Kind, affable, but also very discreet, somewhat self-effacing, even shy.

The “Wagner heir” hesitated for a long time to follow the family path. After his father’s death in 1883, the young boy considered for a while to escape destiny by embracing a career as an architect. But one cannot be born a Wagner from Bayreuth… and become an architect! Siegfried thus inevitably resigned himself. He must become a musician.

First of all, he became a conductor, his learning being done with Hans Richter. This training allowed him to ensure in 1896 the direction of his first Ring, for the in loco resumption of the performances of The Ring.

First of all, he became a conductor, his learning being done with Hans Richter. This training allowed him to ensure in 1896 the direction of his first Ring, for the in loco resumption of the performances of The Ring.

If Richter taught the heir the art of direction, Engelbert Humperdinck, the composer of the famous operas Hänsel and Gretel and The King’s Children (Die Königskinder), taught him the rudiments of composition.

His influence on the work of the Wagner son was very present: the path that Siegfried followed in composition was indeed that of the fairy tale for children with resonance for adults, and treated on a post-Wagnerian music.

His compositions were also very numerous, even if they rarely went past the writing stage (Der Bärenhäuter, 1898, Herzog Wildfang, 1900, Der Kobold, 1903).

Cosima, however, taught her son Siegfried the art of staging, or rather she taught him the only possible staging, that of his deceased revered husband, Master Wagner: this sclerotic art was not very conducive (an euphemism!) to new ideas that tried to break through on the Hill to breathe new life into it.

Let us not even mention the theories that Appia defends: modernity in the lighting effects, refinement of the staging work, the costumes, acting, none of the young Swiss’ theories managed to seduce the “old lady of Bayreuth “. If Siegfried must pursue the quasi-divine task that was devoted to him, it would be by abiding without saying a word to the imperious orders of the old Wagnerian guard, an old guard totally insensitive to this wave of novelty that still surged outside the venerable stage of the Festpielhaus.

It was Gustav Mahler who first shook the tradition on the stage of the Vienna Staatsoper with a Tristan (1903) and then the first two episodes of The Ring drawn by the stage director and decorator Alfred Roller.

From 1912 to 1930, no fewer than twenty productions throughout Germany offered surprised but still conquered spectators a new face, a new conception of Wagner’s work on stage. But to consider such audacity in Bayreuth was hardly conceivable. In the shadow of Siegfried watched Cosima, imperturbably, always staying true to tradition.

From 1912 to 1930, no fewer than twenty productions throughout Germany offered surprised but still conquered spectators a new face, a new conception of Wagner’s work on stage. But to consider such audacity in Bayreuth was hardly conceivable. In the shadow of Siegfried watched Cosima, imperturbably, always staying true to tradition.

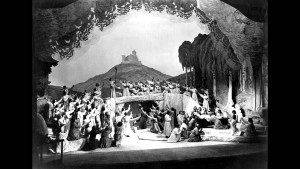

The “unfortunate” Siegfried tried, however, in spite of this imperious gaze on his shoulder, several attempts at a certain novelty, introducing electric lighting on the stage and the hall of the Festspielhaus, realizing little by little three-dimensional productions, refusing – supreme audacity – the ease of recourse to painted canvases. Hunding’s hut, the arrival on stage of a real ship (The Flying Dutchman in its very first staging in 1901) were as many new experiences for the stage director (and for the public) as affronts thrown in the face of the Wagnerian rearguard.

But Siegfried could not be too innovative: if he wanted to stay at the head of the Festival, he would have to accept its rules. And if he was to keep Wagner’s magic alive as it was understood in Bayreuth and fill the coffers largely damaged by the First World War, as a diligent manager he would have to make sure he kept his position. Siegfried only succeeded in changing a few decorative elements in his mother’s authoritative productions (a rock here, a hut there) and he had to wait until the very end of his mandate so that a Tristan in 1927, and especially a Tannhäuser in 1930, Siegfried’s art managed to express itself on stage, not in complete freedom, but with less timidity than in the past.

And it was discovered with these late productions a talent as rarely there was before on the Hill: the Tannhäuser directed by Toscanini in 1930 was a brilliant example of what Siegfried would have wanted to do if he had free reign.

On the other hand, if in the Festival crew nothing (or rather nobody) changed fundamentally, the distributions, however, were pure excellence. Most of the first-time singers – those who performed the roles under the direction of the Master – were gone, and it was the turn of Maria Müller, Friedrich Schorr, Herbert Janssen or of Lauritz Melchior to be in the spotlight of the Festspielhaus. And what a triumph: Wagner’s art was vocally unparalleled in Bayreuth and people came in droves on the Hill!

On the other hand, if in the Festival crew nothing (or rather nobody) changed fundamentally, the distributions, however, were pure excellence. Most of the first-time singers – those who performed the roles under the direction of the Master – were gone, and it was the turn of Maria Müller, Friedrich Schorr, Herbert Janssen or of Lauritz Melchior to be in the spotlight of the Festspielhaus. And what a triumph: Wagner’s art was vocally unparalleled in Bayreuth and people came in droves on the Hill!

But the year 1930 resonated like a double mourning in Wahnfried as well as on the Green Hill. On 1 April, 1930, Cosima, 92 years old, passed away. The old lady’s death, who was no more than a shadow but who still directed the spirit of the Festival with firmness and obstinacy, freed her son who finally felt invested with full powers, he who had never been able to say “no” to the matriarch.

And this famous Tannhäuser performance of 1930 marked his advent, which was unfortunately as quick as a flash! Siegfried could neither enjoy his triumph nor pursue this renewal work: during the rehearsals, Wagner’s son collapsed, victim of a heart attack. While Tannhäuser‘s premiere on 22 July was triumphant and gave back to Bayreuth a forgotten radiance, Siegfried, alone and away from the Festspielhaus, was dying. He died a few days later, on 4 August, only four months after his own mother. Then began for Bayreuth the most troubled period of all its history.

NC/SB

List of reference materials consulted for the realization of Section IV : BAYREUTH

![]()

If you wish to share further information about this article, please feel free to contact us !