VII. WOLFGANG WAGNER’S

VII. WOLFGANG WAGNER’S

“WERKSTATT BAYREUTH” (Bayreuth workshop)

After the premature death of his brother Wieland in 1966, Wolfgang found himself in command, alone, to manage all the responsibilities of a festival that had regained all its pre-war glory.

But the younger brother who grew up in the shadow of the man who had carved out a very important part of it – to the point of taking almost all the credit exclusively for himself – found it difficult to impose himself as the sole administrative and artistic director at the helm of “Bayreuth Ship”. What a heavy burden that was to succeed a giant, let alone a brother. How could one eclipse the talent with which Wieland had imposed himself on the stage of Neues Bayreuth! His opening Ring of 1951, his Tristan (1952), his Lohengrin (1958) and his Master-Singers created the aesthetic norm of the New Bayreuth and served as a reference in terms of modernity in a seemingly inescapable and unsurpassable way. These could just be copied. And this is what was reproached to the timid brother of Wieland, namely in his staging approach of not being an innovator but just a follower.

Yet this breach in modernity that Wieland Wagner opened, Wolfgang tried to keep it up, especially by bringing elements of color where Wieland had only explored halftones, shadows as well as black-and-white. But in 1957 (Tristan), then in 1960 (The Ring), the public was reassured, whereas a few years earlier it had been shocked by the audacity of the elder brother.

However, although already in office, the succession of Wieland in “exclusive” favour of Wolfgang did not go without saying.

As usual over about a century, the Wagner family made it a point to turn this death into the starting point of quarrels and internal rifts. The succession of Wieland Wagner could have seemed completely “settled”: indeed, the “New Bayreuth” granted in 1949 full powers jointly to the two brothers, Wieland and Wolfgang. One of the brothers having passed away, the management seemed to have to return to the one that remained… in this case Wolfgang.

But not all members of the family thought so. Thus Gertrud, widow of Wieland – a dancer who had retired from the stage and seconded him for the choreographies of the productions of Tannhäuser and Parsifal especially – considered that it was legitimate for her to also be at the helm of the Festival. She had, moreover, taken over the productions of her late husband on a few stages in Europe, and had herself signed stage productions strongly inspired by her husband’s style, notably on the stage of the Stuttgart opera, one of his “bastions”. But the Wagner widow did not meet the hoped-for success and failed.

But not all members of the family thought so. Thus Gertrud, widow of Wieland – a dancer who had retired from the stage and seconded him for the choreographies of the productions of Tannhäuser and Parsifal especially – considered that it was legitimate for her to also be at the helm of the Festival. She had, moreover, taken over the productions of her late husband on a few stages in Europe, and had herself signed stage productions strongly inspired by her husband’s style, notably on the stage of the Stuttgart opera, one of his “bastions”. But the Wagner widow did not meet the hoped-for success and failed.

Friedelind, the sister, who had been removed from “power” at the time of the redistribution of the roles in the aftermath of the war, had hoped her time had come and saw an opportunity to rise to the rank of legitimate claimants to the succession. She made her debut by staging a new production of Lohengrin with students from Bayreuth. Too shaky, not professional enough undoubtedly, the project remained dead on arrival and did not accede to the honors of the scene of the Festspielhaus.

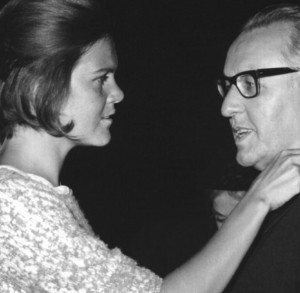

However, if there was a personality that had been unanimous and had gotten all the votes against her and gathered all the hatred of the family, it was Wieland’s last lover, Anja Silja, the divine Freia, the fierce Senta, the chaste Elisabeth… to whom it was hinted that she was from then on “persona non grata“!

However, if there was a personality that had been unanimous and had gotten all the votes against her and gathered all the hatred of the family, it was Wieland’s last lover, Anja Silja, the divine Freia, the fierce Senta, the chaste Elisabeth… to whom it was hinted that she was from then on “persona non grata“!

Resigned, Anja Silja preferred, to avoid any scandal, to leave Bayreuth (she no longer appeared in the distributions starting from 1967) and to enjoy the honors that the audience gave her elsewhere, on other stages, and with the success that we know.

For her part, if Winifred never loved or dubbed the work of her own son (did she not exclaim in the wake of the Parsifal performance of the opening of the New Bayreuth in 1951: “And that, coming from a grandson of Richard Wagner! “), she had quite a hard time concealing her discomfort with this new twist of fate that fell on her family… and on the destiny of the Festival.

Artistically, Wieland‘s death caused a deep shock and marked the history of the Festival with a dark stone and Wolfgang Wagner too closely followed the indications and aesthetic of his brother to alone manage to renew the genre. The years that immediately followed the death of Wieland made for the second time the Festpielhaus a mausoleum: the blind faithfulness of the assistants tried to make the work of the dearly departed live, with energy.

Thus, his last Parsifal was performed until 1973, his ultimate Ring until 1969, his Tristan until 1970. With the same singers (Nilsson and Windgassen renewing each year the miracle of music and images) or many new performers who struggled to match the singers of a golden age that was dying out.

Thus, his last Parsifal was performed until 1973, his ultimate Ring until 1969, his Tristan until 1970. With the same singers (Nilsson and Windgassen renewing each year the miracle of music and images) or many new performers who struggled to match the singers of a golden age that was dying out.

Again, the paradox that followed Richard Wagner’s death emerged: by wanting to make the theatrical art of a being passionate about novelty live, it mummified it. Once again, we were very far from the famous will that Richard Wagner himself had left to his descendants: “Children, make something new!“

Wolfgang Wagner, conscious of this state of both deliquescence and crisis, had to react so as not to see sink the boat of which he was in command. But how? It was then that he had the idea of bringing “new blood” to Bayreuth, notably by entrusting – sacrilegiously – the staging of his grandfather’s operas to newcomers who were not part of the family. These were the new precepts he would try to defend in his undertaking of the “Bayreuth Workshop” (Werkstatt Bayreuth).

1. Wolfgang Wagner’s “Werkstatt Bayreuth”

To open the way for new ideas, new concepts and new perspectives: this was now Bayreuth’s motto. A new theme was found: to invite popular young directors in the field of theatre and opera – outside the family – to bring to the Hill their vision of Richard Wagner’s work.

This tradition is still respected today and the productions of the guest directors mingle with the productions of direct “rightholders”, such as Wolfgang and Katharina Wagner. With the exception of Rudolf Hartmann’s Master-Singers staged for the re-opening of the New Bayreuth in 1951, which was quite classical and respectable, it was August Everding, the “image maker” (which are quite sensible and consensual), who was chosen to be the first “out of Wagner clan” director to bring his ideas to the stage of the Festspielhaus, with two productions: a Flying Dutchman in 1969, then a Tristan and Isolde in 1974. These stage productions turned out to be quite neutral, and if they did not create a scandal, they did not create radiance of the triumphs for the most exciting and most relevant stage productions in the history of the Festival either.

The first scandal came with the Tannhäuser produced in 1972 by Götz Friedrich.

With this new production, the machine of a scenic revival was launched. By presenting a Tannhäuser victim of a society of intolerance with fascistic characteristics (the scenes of Act II at Wartburg showed a uniform society, codified to the extreme and resonated like a direct condemnation of the aesthetic and brutal practices of the Third Reich), the director imposed as a slap to the Wagnerian rearguard, decidedly always as mistreated!

With this new production, the machine of a scenic revival was launched. By presenting a Tannhäuser victim of a society of intolerance with fascistic characteristics (the scenes of Act II at Wartburg showed a uniform society, codified to the extreme and resonated like a direct condemnation of the aesthetic and brutal practices of the Third Reich), the director imposed as a slap to the Wagnerian rearguard, decidedly always as mistreated!

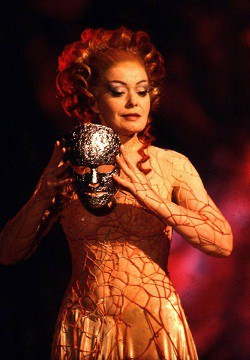

This high-quality production in which distinguished themselves performers such as Gwyneth Jones (who played both Venus AND Elisabeth), Spas Wenkoff or Bernd Weikl disturbed the audience so much that the final from the second performance had to be rearranged.

This high-quality production in which distinguished themselves performers such as Gwyneth Jones (who played both Venus AND Elisabeth), Spas Wenkoff or Bernd Weikl disturbed the audience so much that the final from the second performance had to be rearranged.

And the director explained his vision of Tannhäuser: “This Tannhäuser that Wagner proposes to us possess a greatness which, although already historical, remains current because it is inseparable from the struggle the hero desperately engages in” (Götz Friedrich on the production of Tannhäuser in Bayreuth, 1972).

2. The credo of modernity

Modernity, or better yet, atemporality and even universality of action, the word was said: it became henceforth a sacrosanct credo on the Hill.

The most significant scandal of this new era conducive to change was the now famous Centennial Ring (1976) led by the Chéreau–Boulez tandem. The brilliant party announced for the celebration of the centennial of the Festival indeed turned into the most total chaos.

After an opening night of the Festival that presented, under the direction of Karl Böhm, the scene of the Festwiese extracted from The Master-Singers in a “classicism” close to the naïve imagery staged by Wolfgang Wagner, the curtain opened on one of the most relevant visions (and one of the most impertinent with regard to the Wagnerian rearguard still stationed in Bayreuth) of the century.

Gone were, for sure, the horned helmets and the cups of mead, as well as the huts and the animal skin, but also so was Wieland Wagner’s abstraction; time to re-read, with strength, sets and costumes all borrowed from the XIXth century

Because if the door had been opened with the Friedrich’s Tannhäuser in 1972 to the atemporality of the myths in Richard Wagner’s work, the Festival of 1976 from then on opened on its re-reading in light of the narration of the emergence (and decline) of the great Western civilizations of the contemporary era.

Indeed, what is more universal than the myth of gold stolen by a malicious spirit and consumed with greed at the expense of the noblest of sentiments, Love?

But any scandal in Bayreuth – as was often the case elsewhere when it came to Wagner’s work – quickly transformed into triumph: when the curtain fell down after the last performance of Twilight of the Gods, after five consecutive years during which the Centennial Ring had been hated and vilified, it was more than an hour of encores that saluted the miracle of, henceforth, one of the strongest productions of the Festival.

Strengthened by these first scandals that led to triumph, Wolfgang Wagner continued his idea of bringing new blood to his great “makeover” undertaking of the Festival.

Strengthened by these first scandals that led to triumph, Wolfgang Wagner continued his idea of bringing new blood to his great “makeover” undertaking of the Festival.

The Flying Dutchman gamble paid off in the psychoanalytic re-reading proposed by Harry Kupfer (1978), the ecstatic Tristan by Jean-Pierre Ponnelle (1982), Werner Herzog’s romantic Lohengrin (1987), or Kupfer’s Ring (1988), all of which came directly from the post-industrial era.

But also failures – an inevitable corollary of risk – such as the dull and bland Parsifal by Götz Friedrich (1982), and like the Ring productions that followed the one by Chéreau: one, voluntarily naturalist – Peter Hall (1983) – the following , losing themselves in vain in search of a language or a conductive idea like those of Alfred Kirchner (1994) or more recently of Tankred Dorst (2006).

But also failures – an inevitable corollary of risk – such as the dull and bland Parsifal by Götz Friedrich (1982), and like the Ring productions that followed the one by Chéreau: one, voluntarily naturalist – Peter Hall (1983) – the following , losing themselves in vain in search of a language or a conductive idea like those of Alfred Kirchner (1994) or more recently of Tankred Dorst (2006).

For his part, imperturbable, Wolfgang Wagner continued to develop his aesthetic and theatrical concept inherited from his brother’s learning with stage productions – The Master-Singers (1981), Parsifal (1989) – from then on synonymous with “classics“. It took almost thirty years for Wieland’s art, once innovative and provocative, later stuck and almost immutable – contrary to what his genitor himself would have liked – to fall into disuse.

As for the vocals, the Festival was from that moment plunged between the shortage of great Wagnerian singers (the Nilsson, Windgassen, Rysanek, King were no longer) and a certain obligation to build finds on the Green Hill.

As for the vocals, the Festival was from that moment plunged between the shortage of great Wagnerian singers (the Nilsson, Windgassen, Rysanek, King were no longer) and a certain obligation to build finds on the Green Hill.

Thus newly found artists such as Waltraud Meier (incredible Isolde alongside Siegfried Jerusalem’s Tristan, a role she played on the Hill for 6 years in the production by Heiner Müller), Deborah Polaski, Poul Elming, Siegfried Jerusalem, Manfred Jung or even Violeta Urmana would see their debut on stage hailed as the renaissance of the interpretation of Richard Wagner’s art.

It was in this halftone situation that Wolfgang Wagner (who died two years later, on 21 March, 2010 in Bayreuth) left the Festival in the hands of Katharina, his own daughter, and her half-sister Eva Wagner-Pasquier, on 1 September, 2008.

It was in this halftone situation that Wolfgang Wagner (who died two years later, on 21 March, 2010 in Bayreuth) left the Festival in the hands of Katharina, his own daughter, and her half-sister Eva Wagner-Pasquier, on 1 September, 2008.

Indeed, marked by the setbacks of his succession to his brother, Wolfgang Wagner, at odds with his son, daughter, niece… had, since taking control of the Festival, modified the statutes of the festival, transferring the legal powers of the Festival and of its buildings (Festspielhaus and Villa Wahnfried) to the Richard-Wagner Foundation in Bayreuth, whose board of directors includes members of the Wagner family and representatives of the State. His own succession was thus simplified.

NC/SB

List of reference materials consulted for the realization of Section IV : BAYREUTH

![]()

If you wish to share further information about this article, please feel free to contact us !