If Wagner was the cultural and musical chronicler of his time, if he remained a revolutionary activist, he had also gone into the act of police, and if he was finally his master of Bayreuth celebrated as the one of the major artist of his At the time, the illustrious composer did not live before a man made of chair and blood, animated by passions, with a sometimes violent, sometimes facetious, and sometimes tender character.

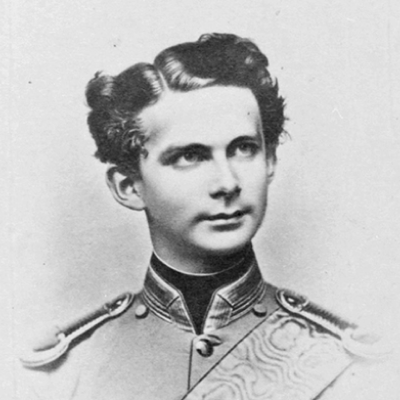

LUDWIG II of BAVARIA (King)

(born on August 25. 1845 – died on June 13. 1886)

King of Bavaria (from 1864 until his death in 1886)

If there was a patron in Richard Wagner’s life, it was King Ludwig II of Bavaria. A “fairytale king“, as his loyal people affectionately nicknamed him, who had the misfortune of very often confusing his romantic and artistic dreams with the politics of a kingdom that he alone had to take on very young.

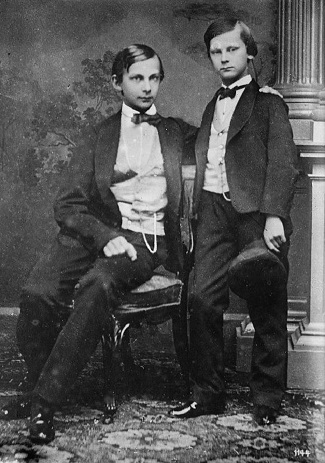

The relations between the young and fiery monarch and the composer went through a host of considerable ordeals, going from the most inflamed (platonic) passion to the deepest enmity. If one can sometimes get lost in the details of the history of this exalted friendship, one cannot forget that without the king’s existence and unfailing support, Richard Wagner’s work would have never become what it is.

![]() A “fairytale King” straight from a Wagnerian dream

A “fairytale King” straight from a Wagnerian dream

The son of King Maximilian II of Bavaria and Marie of Hohenzollern, princess of Prussia, the future King Ludwig II of Bavaria was born on 25 August, 1845 on a beautiful summer day in a setting of legends: the Castle of the Nymphs (the Nymphenburg Castle, close to Munich).

Deeply rooted in the Catholic tradition, the kingdom of Bavaria had already been shaken by scandals. Indeed, while the young prince was not a year old yet, his grandfather, King Ludwig I of Bavaria, became during his last years besotted with an actress named Lola Montès, which strongly displeased the conservative Bavarian people. The monarch preferred to abdicate rather than renounce his passion for the young adventurer who, as for her, undoubtedly had dreamed of a throne! Ludwig, when he publicly displayed in turn his relationship of exaggerated affection for Richard Wagner, was therefore in line with a certain family tradition… And when the favourite Wagner was singled out – who, overstepping the monarch’s favours, meddled in politics a little too much in the eyes of the people – the latter would be given the nickname “Lolus“, reminding the young monarch of the excesses of his own grandfather who, before him, had succumbed in his greatest misfortune to the charm of the “artists”.

Ludwig I having abdicated, Maximilian, Ludwig’s father, therefore prematurely acceded to the throne of Bavaria.

Maybe by a see-saw effect, Maximilian, having suffered from the liberty of his father’s morals, imposed a very rigid universe for the education of the young Ludwig.

Wanting to keep his son away from the “worst” path that a monarch could follow, he imposed a particularly strict discipline, devoid of demonstration of unnecessary affection.

He had to spend hours studying science and literature, under the awkward – and often obstinate – eyes of private tutors who were not particularly attentive of the young boy’s exacerbated sensitivity. If the prince was as unreceptive to sports education as he was to learning sciences such as technique or mathematics, his “elective affinities” were on the other hand already very pronounced for literature, mythology (a common trait with the young Wagner’s education) as well as religious history and foreign languages, and in particular, French.

He had to spend hours studying science and literature, under the awkward – and often obstinate – eyes of private tutors who were not particularly attentive of the young boy’s exacerbated sensitivity. If the prince was as unreceptive to sports education as he was to learning sciences such as technique or mathematics, his “elective affinities” were on the other hand already very pronounced for literature, mythology (a common trait with the young Wagner’s education) as well as religious history and foreign languages, and in particular, French.

Solitary, secretive, with a touchy character, the future monarch – who was made from his earliest childhood to understand the burden and weight of his future crown – spent his time between the Munich Residence and the Hohenschwangau Castle, in the Bavarian Alps, near Füssen.

A Wagnerian place if ever there were one, a royal villa acquired in 1832 by his father in the form of a ruin which he restored at great expense in a neo-Gothic style in 1837: directly linked to the Germanic legends of Lohengrin,

The Knight of the Swan, and Tannhäuser, this place quickly became Ludwig‘s favourite place (he would call it “the paradise of my childhood“).

It was in this environment conducive to romanticism and to the most exalted dreams that Ludwig discovered Richard Wagner’s art: the theoretical treatises, first of all, with the reading of The Artwork of the Future, in 1857, then the opera, on 2 February, 1861: it would be… Lohengrin.

It was in this environment conducive to romanticism and to the most exalted dreams that Ludwig discovered Richard Wagner’s art: the theoretical treatises, first of all, with the reading of The Artwork of the Future, in 1857, then the opera, on 2 February, 1861: it would be… Lohengrin.

Just three years later, the young Ludwig became Ludwig II of Bavaria, and acceded to the throne at the age of eighteen. Young, slender (he was 1m90), irresistibly beautiful, the young king instantly conquered the heart and the support of the Bavarian people. But if he was conscious of his obligations to the kingdom, the young monarch’s heart wholly tended towards… Richard Wagner!

![]() Ludwig II and Richard Wagner, the story of a passion

Ludwig II and Richard Wagner, the story of a passion

He had barely acceded to the throne (Ludwig was crowned on 10 March, after his father Maximilian died) when the young monarch felt invested with a “mission”: to save the composer Richard Wagner, whose work he already admired and whose recent misfortunes he had heard about.

He had barely acceded to the throne (Ludwig was crowned on 10 March, after his father Maximilian died) when the young monarch felt invested with a “mission”: to save the composer Richard Wagner, whose work he already admired and whose recent misfortunes he had heard about.

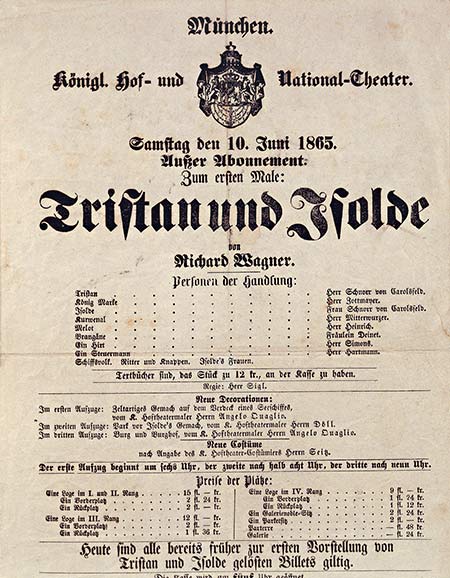

And indeed, at the beginning of 1864, the composer was doing really badly: Wagner was then in Vienna and tried to gather all the necessary elements for the creation of Tristan and Isolde, but for lack of performers and of an orchestra measuring up to the – immoderate – height of the work, the company “got bogged down“.

And the artistic setbacks preceded the inevitable financial debacles the composer was accustomed to.

Fleeing the creditors who pursued him, he slipped away to escape from the police… and in doing so he also shied away from Pfistermeister, Ludwig II of Bavaria’s aulic counsellor, sent by the sovereign in search of the composer, who was definitely elusive. The game of hide-and-seek between the composer and the aggrieved minister that lasted almost a month ended on 3 May, 1864… in Stuttgart! When he was on the verge of fleeing again, Richard Wagner found himself face-to-face with Pfistermeister who gave him a portrait of the young monarch and a (first) gift: a sumptuous ruby inserted in a ring. The king demanded Wagner to his court and as quick as possible. Wagner, who immediately replied with a letter to the monarch (“I send you the tears of the most celestial emotion to tell you that the miracles of poetry have entered as a divine reality in my poor life avid for love”), hurried to go to Munich. It was the end of the wandering for the composer short of recognition.

Upon his arrival in Munich, Ludwig II wanted Wagner to be by his side and “installed” him near his residence, the Berg castle, on the shores of Lake Starnberg, in the replica of a Swiss chalet named “Villa Pellet”. And offered his “royal protege” the first allowances coming directly from his personal treasury, all more important than the previous ones.

Upon his arrival in Munich, Ludwig II wanted Wagner to be by his side and “installed” him near his residence, the Berg castle, on the shores of Lake Starnberg, in the replica of a Swiss chalet named “Villa Pellet”. And offered his “royal protege” the first allowances coming directly from his personal treasury, all more important than the previous ones.

To this providential monarch who imposed himself in Wagner’s life like a miracle, Wagner related his life, his adventures to a teenager eager to always know more about him. He promised him the complete account of his life in an autobiography that would be specially dedicated to him – it would be Mein Leben (My Life) – but also operas, many operas to satisfy the fantasies of the young king, or even… a theatre?

Very quickly, the relationship between the monarch and the composer inevitably evolved into an ascendancy that the king’s entourage dreaded. More than thirty years his elder, fiercely charismatic, Wagner had little difficulty in exercising his influence with the sovereign, and this all the more “easily” that he worked on the particularly fertile ground of an exhilarated mind for too long contained. Thanks to the sovereign’s support, the “Tristan affair” – impossible to implement in Vienna – was now almost a “formality”. Certainly, at great expense: more than seventy rehearsals with the orchestra for a work on which critics emitted the biggest reservations. But nothing was too good to satisfy the demands (whims) of a monarch and his royal protege.

If the work was described as indecent, if the music was not really conducive to the immediate support of the public, the creation of Tristan and Isolde on 10 June, 1865, from then on under the king’s protection, caused a commotion: if the king loved it, the people, under its monarch’s spell. King loves, the people, always under the spell of his monarch, had to comply.

If the work was described as indecent, if the music was not really conducive to the immediate support of the public, the creation of Tristan and Isolde on 10 June, 1865, from then on under the king’s protection, caused a commotion: if the king loved it, the people, under its monarch’s spell. King loves, the people, always under the spell of his monarch, had to comply.

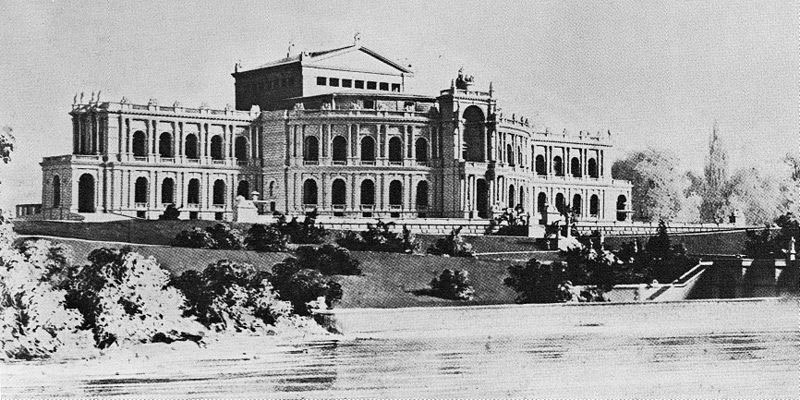

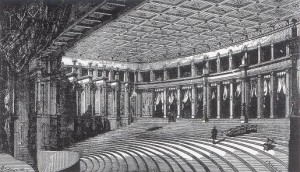

Naturally, Wagner did not want to stand in the good way of fortune that smiled on him: parsimoniously, he suggested to Ludwig the dream of a theatre that would be specially designed to produce his own works. To do so, the composer needed science represented by his longtime friend, the architect Gottfried Semper, to design a Festtheater – well before a Festspielhaus – that should be erected on the banks of the Isar. The sovereign, conquered in advance, could not resist the advent of what he regarded as his own dream. Who, the sovereign-patron or the composer-protege, would have held the reins in this adventure the longest? The power relation would keep changing hands during the coming decade.

Richard Wagner did not care about the gossip that swelled in the streets of Munich, and that spread like wildfire. But the people got tired of seeing that nothing was too good to satisfy the material well-being of the composer and showed itself to really be more and more hostile to this couple that he publicly displayed with Cosima, the wife of his best friend and conductor, Hans von Bülow.

According to the terms of a new contract ratified on 18 October, 1865, the king paid Wagner the exuberant sum of 40,000 guilders.

According to the terms of a new contract ratified on 18 October, 1865, the king paid Wagner the exuberant sum of 40,000 guilders.

The Finance Office of the kingdom knew that it was to Cosima, who managed the artist’s fortune, that the sum in hard cash was to be handed over. She had to transport it in a fiacre to Wagner’s new home, Briennerstrasse in Munich. But the Office committed a faux pas: to the “treasurer” of the “Wagner industry“, the Treasury offices claimed they did not have enough banknotes to give. Wagner (innocently?) stepped up to the plate and complained to the monarch.

It was truly too much for the good Bavarian people who, a year before, was moved by the familiarity with which the composer had called the king “My boy“. It was, with his hands tied, that Ludwig II had to renounce to the presence in Munich of this guest, so desired that it got embarrassing: he had to reluctantly pronounce his disgrace. Wagner again went into exile. In Switzerland, and more specifically, in Tribschen.

![]() Munich-Tribschen- Bayreuth:

Munich-Tribschen- Bayreuth:

from artistic inspiration to financial intrigue

If Ludwig II had to yield to the pressure of his people and his government and to physically remove Richard Wagner, he did not remain any less close to his heart. In the Tribschen Villa, where he was now settled with Cosima (who was still married to von Bülow), the composer recovered as best as possible from his disgrace and redoubled efforts and artistic inspiration.

If Ludwig II had to yield to the pressure of his people and his government and to physically remove Richard Wagner, he did not remain any less close to his heart. In the Tribschen Villa, where he was now settled with Cosima (who was still married to von Bülow), the composer recovered as best as possible from his disgrace and redoubled efforts and artistic inspiration.

Even if he was away from the court – temporarily – Wagner seemed to remain rather confident about his ascendancy over Ludwig II of Bavaria. Besides, as soon as his protege was snatched from him by public force (reason?) , as soon as the absence of the “Friend” became unbearable to the monarch. Richard Wagner – who was very accustomed to the difficulties of emotional relationships and to the art of maintaining them for that matter, knew perfectly well that in every form of love, absence and dissatisfaction always conquer. While he was in full composition of The Master-Singers of Nuremberg, Wagner, from his villa in Tribschen, tried to manipulate the king and advised him.

But if he was exhilarated and dedicated a limitless passion to the composer, Ludwig was a wise politician.

He found himself, as a pacifist, having to face conflicts generated by old alliances. Indeed, traditionally allied to Austria, Bavaria had come into conflict with Prussia when it attacked Austria. But Ludwig II behaved in such a way that Bismarck did not hold it against him.

It was at this time that Ludwig II got engaged to Sophie-Charlotte in Bavaria, the youngest sister of Sissi, also his cousin. A young woman whose destiny would not be the least tragic of this truly cursed family, a fine musician and a fervent admirer of Wagner, she had already turned down several suitors, having witnessed her sisters’ certainly brilliant but disastrous marriages.

It was at this time that Ludwig II got engaged to Sophie-Charlotte in Bavaria, the youngest sister of Sissi, also his cousin. A young woman whose destiny would not be the least tragic of this truly cursed family, a fine musician and a fervent admirer of Wagner, she had already turned down several suitors, having witnessed her sisters’ certainly brilliant but disastrous marriages.

When Ludwig II asked her to marry him, Sophie Charlotte rejoiced.

But becoming aware of her nature, Ludwig repeatedly postponed the wedding before splitting for good.

Relieved that he escaped from this “catastrophe”, he learned of Wagner’s betrayal and kept a great grudge against him: indeed, while the king, on the basis of the evidence provided by the composer and the husband, defended Cosima’s honour, even going as far as writing a letter prohibiting any gossip about her, he became aware of the situation.

His love for Wagner cooled, but did not necessarily go out.

Increasingly seeking to distance himself from reality, Ludwig II, strongly attached to France, took very badly that he had to ally himself with Prussia in 1870.

Increasingly seeking to distance himself from reality, Ludwig II, strongly attached to France, took very badly that he had to ally himself with Prussia in 1870.

The Lion of Bavaria was wounded. His monarchy no longer had any sense, and the crowning of the Emperor William put an end to his political power.

He was able to preserve the identity of Bavaria, but these few years were gruelling. He escaped with passion – and madness – in the advent of his most megalomaniac dreams. To the construction of the craziest castles directly from the Wagnerian imagination (Neuschwanstein or even Linderhof and his follies such as the underground Venus grotto or even Hunding’s hut), Ludwigadded the demand of another dream: the creation of Wagner’s Ring. “How can it be done without a theatre?” retorted the composer.

Then began one of the tightest artistic tugs of war in the History of Art: on the one hand, the king, protector, patron, having bought the performance rights of the first two completed parts of the Wagnerian epic (The Rhinegold and The Valkyrie), on the other hand, a composer who held back his inspiration and his pen (at least officially) so as not to let the ink of the last two parts flow (Siegfried and The Twilight of the Gods) as long as he would not have his own theatre!

No one would truly emerge victorious from this merciless struggle, or rather… both.

No one would truly emerge victorious from this merciless struggle, or rather… both.

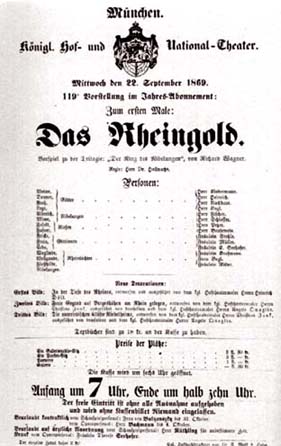

Ludwig II, to whom the Council of Ministers refused to release the funds necessary to build the Festtheater in Munich, impatient, went so far as to defy the will of his protege and get “his” Ring staged (or at least the first two parts whose rights he had) successively on 22 September, 1869 for The Rhinegold, and on 26 June, 1870 for The Valkyrie.

Against the recommendation of the composer who redoubled fury since his exile from Tribschen.And ardour to compose the next two parts for a Festival that he imagined outside the jurisdiction of Munich to escape the control of the sovereign. It would be in Bayreuth.

![]() Bayreuth and the Flight of the Swan

Bayreuth and the Flight of the Swan

On his way to Bayreuth, Wagner wanted to free himself from the royal “dependence”.

On his way to Bayreuth, Wagner wanted to free himself from the royal “dependence”.

But even while struggling through thick and thin to try to raise the necessary funds for the construction of his own Festival Theatre, Richard Wagner failed.

At the beginning of 1874, at the most critical moment in the “great enterprise” that represented the construction of the ideal theatre, and while Wagner foresaw failure, King Ludwig II again came to the rescue of his friend in distress.

In a letter dated 25 January of that year, the king took action and re-engaged in a dialogue with his protege: “No! No and no! That is not how it should end: it is necessary to save it! Our project must not fail!” And the king paid from his personal treasury the necessary funds to save the ship in turmoil, against the recommendation of the Court administration that, a few days earlier (January, 6.), had refused to take on the financial guarantee necessary to the Bayreuth Festival. It was thus reconciled that the two men set up a meeting for the creation in loco of the entirety of the four parts composing The Ring. But increasingly withdrawn, the king came almost incognito to participate in this great celebration of the Art where were invited all the crowned heads of Europe. Incidentally, he only attended the dress rehearsals, from 6 to 10 August, so as not to have to face the obligations of a protocol that he fled more and more.

The “Bayreuth adventure” was launched and was able to see the light of day thanks to the monarch’s support. While in Munich on the occasion of a party given in his honour, Wagner was summoned by the king to attend, on 10 November, 1880, a private (and nocturnal) performance of Lohengrin at the Court Theatre. The two friends were alone in the theatre, with the exception of a few rare witnesses of this strange performance, like Cosima and her daughters hidden behind boxes, invisible to the king’s eyes.

Two days later (12 November), the monarch demanded that Wagner direct a private concert and make him listen to the prelude of Parsifal. Wagner complied with all the religiosity that was necessary. At the end of this private listening session, Ludwig II asked Wagner to direct for him the prelude of Lohengrin, the opera that, a few years before, had united the two men, “to compare”, Wagner understood that they no longer shared the same artistic common ground. The composer, once again offended, passed the baton to Hermann Levi.

And while Ludwig II of Bavaria’s soul rose in the kingdom of the Grail with hints of the mystical prelude of Lohengrin, Wagner left the theatre without even a farewell to the monarch. The two men would not see each other again.

And while Ludwig II of Bavaria’s soul rose in the kingdom of the Grail with hints of the mystical prelude of Lohengrin, Wagner left the theatre without even a farewell to the monarch. The two men would not see each other again.

And the monarch, adopting an increasingly strange and solitary behaviour, close to madness, would not attend the creation of Parsifal.

When, in February 1883, Ludwig II learned of Wagner’s passing, the monarch felt terrible grief and sense of abandonment. In the Neuschwanstein castle, where he now resided most of his time, away from the Munich court and fleeing his obligations, he covered with a black crepe veil the piano on which the composer once played for him.

Declared mentally unfit to rule, King Ludwig II of Bavaria was arrested by the forces of his own government and committed, on 12 June, 1886, in the Berg castle where he was placed under house arrest. A Lion of Bavaria, much less a swan, could not live long captive. On the very day after his arrest, the king asked to be granted an evening walk during which he was accompanied by his doctor, Doctor Bernhard von Gudden. The bodies of the monarch and his doctor were found lifeless shortly afterwards. Crime, suicide, double crime, double suicide? The mystery surrounding the death of King Ludwig II of Bavaria on this night of 13 June, 1886 remains unexplained, elusive, just like the personality of a monarch who, though loved by his people, had never managed to be understood, and who went as far as to sacrifice his own destiny as a king for his dream, but also for the glory of the art of a composer whom he had passionately loved throughout his life.

Declared mentally unfit to rule, King Ludwig II of Bavaria was arrested by the forces of his own government and committed, on 12 June, 1886, in the Berg castle where he was placed under house arrest. A Lion of Bavaria, much less a swan, could not live long captive. On the very day after his arrest, the king asked to be granted an evening walk during which he was accompanied by his doctor, Doctor Bernhard von Gudden. The bodies of the monarch and his doctor were found lifeless shortly afterwards. Crime, suicide, double crime, double suicide? The mystery surrounding the death of King Ludwig II of Bavaria on this night of 13 June, 1886 remains unexplained, elusive, just like the personality of a monarch who, though loved by his people, had never managed to be understood, and who went as far as to sacrifice his own destiny as a king for his dream, but also for the glory of the art of a composer whom he had passionately loved throughout his life.

NC.

If you wish to share further information about this article, please feel free to contact us !