If Wagner was the cultural and musical chronicler of his time, if he remained a revolutionary activist, he had also gone into the act of police, and if he was finally his master of Bayreuth celebrated as the one of the major artist of his At the time, the illustrious composer did not live before a man made of chair and blood, animated by passions, with a sometimes violent, sometimes facetious, and sometimes tender character.

THOSE RELATED ARTICLES MAY

INTEREST YOU

YEAR 1883

YEAR 1883

During the first days of 1883, Richard Wagner learned the invention of the phonograph, this news the unworthy as it saddened. February 6, 1883 (Mardi Gras Evening) The Carnival is in full swing and the Wagners are St. Mark’s Square where they see the procession of Prince Carnival (Read More)

ELEGY WWV93

ELEGY WWV93

This fragmentary work (album sheet) in A flat major seems to have been written by Wagner in 1869. This page was long considered a late work (see the last notes he drew in Venice before his death in 1883). Wagner played it said the day before his death. (Read more)

TRISTAN AND ISOLDE

TRISTAN AND ISOLDE

Richard Wagner’s seventh opera, Tristan and Isolde (WWV 90) is the fourth in the so-called period of maturity of the composer and the first created under the patronage of King Ludwig II of Bavaria. It is also the only work resulting from an order in the career of the composer: March 9, 1857, (Read more)

PÄTZ Johanna Rosine

(19. September 1774 – 9. January 1848)

Wife of Carl Friedrich Wagner and Richard Wagner’s mother

Richard’s mother was born in Weissenfels, about thirty kilometers south-west of Leipzig, on 19. September, 1774 [1]. She was the sixth child (and the fourth child that lived) of the baker or miller Johann-Gottlob Pätz and his first wife, Dorothea Erdmuthe, née Iglisch, daughter of a tanner. The latter died when Johanna was fourteen. Her father remarried on 28 October, 1788 (and entered into a third marriage in 1795). Johanna surrounded her genealogical tree with a certain mystery, although the master baker recognized her as his legitimate daughter.

She told her children that her maiden name was Perthes. They learned that it was actually pronounced Petz. Richard himself hesitated between three spellings: Pätz, Petz or Beetz [2]. Was it to hide the difference in social condition between her family and her husband’s? She said that she had been brought up not by her parents, but in one of the best boarding schools in Leipzig. This unusual education at that time for the daughter of a craftsman would have been made possible by the solicitude of a high-ranking protector, « a great friend of her father. This friend […] was a prince of Weimar who had done many favours to his family[3] » Wagner told us in Mein Leben. His education would have been interrupted by the sudden death of this friend.

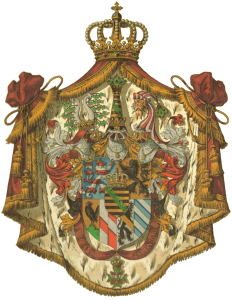

Some biographers [4], especially Houston Stewart-Chamberlain (Eva’s husband, Richard’s second daughter), concluded that Johanna Rosine could have been the natural daughter of Prince Friedrich Ferdinand Constantin of Saxe-Weimar (1758-1793), the only brother of Grand Duke Karl August (1757-1828), reigning prince and benefactor of Goethe. Chamberlain, in order to direct the presumption of paternity on the personality of Prince Constantin, did not hesitate to make Wagner’s mother four years younger, and could assert unscrupulously that the lineage of the master of Bayreuth dated back to the dawn of the Middle Ages.

It has since definitively been proved, in part thanks to the work of Otto Strobel, archivist of Bayreuth and curator of the Richard Wagner Museum in the 1930s, that the paternity of the Prince of Weimar is excluded: he was only fifteen years old when Johanna Rosine was born and lived under close surveillance in Weimar, a city he never left during those years… How did the attention therefore focus on Prince Constantin? In 1981, with his talent as a novelist, Martin Gregor-Dellin recounted in his biography: « Maybe at fifteen, Johanna brought to the poets their morning bread at the inn. It is likely that Schiller, Körner and Humboldt were staying in Weissenfels in the previous years, probably since 1789. […] It cannot be precluded that one of them noticed, in the amateur theatre of Weissenfels, the acting talent of the graceful and pretty Johanna Rosine. It is possible that it was communicated to Prince Constantin de Weimar, who was competent for all things related to theatre of his state. If Prince Constantin had the young Johanna raised in Leipzig, a city open to theatre, this could also explain that this education was interrupted at his death in 1793 [victim of an epidemic in a military camp] [5]». A troubling explanation, since Johanna Rosine seems to have had no further training, she left school in 1789. Something her son confirmed evoking a very inadequate training and education; and indeed her German was terrible… And what if Johanna was neither the daughter nor the protege of the Prince of Weimar, but his mistress!

It has since definitively been proved, in part thanks to the work of Otto Strobel, archivist of Bayreuth and curator of the Richard Wagner Museum in the 1930s, that the paternity of the Prince of Weimar is excluded: he was only fifteen years old when Johanna Rosine was born and lived under close surveillance in Weimar, a city he never left during those years… How did the attention therefore focus on Prince Constantin? In 1981, with his talent as a novelist, Martin Gregor-Dellin recounted in his biography: « Maybe at fifteen, Johanna brought to the poets their morning bread at the inn. It is likely that Schiller, Körner and Humboldt were staying in Weissenfels in the previous years, probably since 1789. […] It cannot be precluded that one of them noticed, in the amateur theatre of Weissenfels, the acting talent of the graceful and pretty Johanna Rosine. It is possible that it was communicated to Prince Constantin de Weimar, who was competent for all things related to theatre of his state. If Prince Constantin had the young Johanna raised in Leipzig, a city open to theatre, this could also explain that this education was interrupted at his death in 1793 [victim of an epidemic in a military camp] [5]». A troubling explanation, since Johanna Rosine seems to have had no further training, she left school in 1789. Something her son confirmed evoking a very inadequate training and education; and indeed her German was terrible… And what if Johanna was neither the daughter nor the protege of the Prince of Weimar, but his mistress!

This is what Gregor-Dellin brilliantly demonstrated, based on numerous documents from the archives of the Grand Duke’s treasurer, mentioning the pensions granted to the favorites and to his mistresses from the petty bourgeoisie and their illegitimate children, in an article published in 1985 (thus subsequent to his biography…) titled: Results of recent research on Wagner (the mystery of the mother) [6]. It turns out that the prince, who had become general of the cavalry division in the army of the prince-elector of Saxony, lived for quite some time, during the year 1790, and twice in Weissenfels, including once (from June to September) not far from the Pätz bakery. It was at this moment that the liaison between the prince and the baker’s daughter began.

Here is what the German biographer stated to us: « Constantin moved his dear Johanna Rosine in Leipzig, with her consent, and not without having probably slightly changed her last name; however, he placed her, not in a distinguished institution, but with a certain lady Sophie Friederike Hesse [7]. Johanna Rosine also received money for her toilette and jewellery, and if Constantin made sure she was given elocution, writing and deportment lessons, it was certainly not for noble purposes or to prepare an acting career, but simply to have a mistress worthy of his rank. She also was not given a high allowance […], since the liaison remained without consequence [8]». After the departure of Prince Constantin for the war, followed by his death in 1793, the young Johanna was abandoned to her fate.

Gregor-Dellin went on to say: “The secret council, of which Goethe was a member, made the following decision in 1793: the daughter of the baker Bezin, of Weissenfels, at the time in a boarding house with a certain lady Hessin in Leipzig, received for the last time the fifty Reichtalers due to the St Michel and was abandoned to her fate [9]“. The latter was named Carl Friedrich Wagner, whom she married on 2 June, 1798. It is this succession of events that explains why Johanna remained enigmatic, as Wagner noted in Mein Leben, about her name, her age and her origins. In his autobiography, he never evoked his maternal grandparents. It seems that Johanna Rosine had broken all ties with her family in Weissenfels, that she never gave her children the opportunity to visit her hometown; where she was only a kept daughter of a baker…

Gregor-Dellin went on to say: “The secret council, of which Goethe was a member, made the following decision in 1793: the daughter of the baker Bezin, of Weissenfels, at the time in a boarding house with a certain lady Hessin in Leipzig, received for the last time the fifty Reichtalers due to the St Michel and was abandoned to her fate [9]“. The latter was named Carl Friedrich Wagner, whom she married on 2 June, 1798. It is this succession of events that explains why Johanna remained enigmatic, as Wagner noted in Mein Leben, about her name, her age and her origins. In his autobiography, he never evoked his maternal grandparents. It seems that Johanna Rosine had broken all ties with her family in Weissenfels, that she never gave her children the opportunity to visit her hometown; where she was only a kept daughter of a baker…

The intrusion of death within the family circle marked the first months of Richard’s existence. His father succumbed at the age of forty-three to epidemic typhus. The epidemic had broken out in the aftermath of the fighting in the bloody battle of the Nations that took place in Leipzig from 16 to 19 October 1813. The hospitals in the city were unable to receive all the wounded, who thus were rushed in churches and schools. Many corpses could not have been buried, and the waters of the Elster were filled with corpses of men and horses. Inevitably, malnutrition, promiscuity and defective hygiene favoured the occurrence of an typhus epidemic.

On 4 November, was counted the death of more than 20,000 people in this town. Hoffmann, who was in Dresden when the epidemic broke out, noted the symptoms in his diary, “headache, dizziness, numbness, death, all within a few hours [10]“. Friedrich Wagner, weakened by the overwork imposed by the police service linked to the disorders of war, was infected by the illness and died on 23 November, 1813. He left nothing to his youngest son, then six months old, not even a portrait… The child would only know him through the distorting mirror of the family discourse. Johanna published an obituary in the Leipziger Zeitung stating that he had been « the victim of his duty… too soon departed for me and my eight dependent children[11]“.

After the death of its chief, the Wagner family, torn away from bourgeois security, was threatened with total dispersion. Johanna Rosine was thirty-nine. In such troubled times, she was alone or almost, without resources (apart from the meager pension paid by the administration), with the burden of raising three sons and four daughters (in 1813, Ottilie was two years old, Klara six, Luise eight, Julius nine, Rosalie ten and Albert fourteen). Out of all the children by the couple, a son Gustav, born in 1801, died at the age of seven months; a daughter, Theresia, did not survive her fourth year, swept away by an epidemic on 19 January, 1814. Johanna could not count on the support of her brother-in-law, Adolf, who lived withdrawn from the world or her sister-in-law, Friedericke. Ludwig Geyer immediately rescued his friend’s widow. He was at first only able to take care of the family through financial assistance. The return of peace in Germany, the promotion to the rank of Court actor in Dresden allowed Geyer to claim Johanna and her children. After a short engagement, they married on 28 August, 1814, in Pötwitz, near Weissenfels. Richard, aged 14 months, once again had a father and a safe home, this time in Dresden. On 26 February, 1815 was born Cäcilie, the legitimate daughter of Geyer and Johanna.

« My mother – a woman! [12] »

The psychological ramifications of his relationship with his mother are not any less complex. At the time when she became a part of Wagner’s memory – she was already old when he was born -, headaches compelled her to wear a bonnet constantly; the painting by Ludwig Geyer immortalised her in this aspect. Wagner confided in his autobiography: “I could not keep the image of a young and gracious mother. The troubles that agitated her in the middle of a large family (of which I was the seventh living member), the difficulties she had in providing for us and sacrificing to a certain decorum, in spite of very limited means, hardly left her with the leisure to manifest those outpourings of tenderness that are peculiar to a mother. I barely remember having received a caress from her: on the other hand, it was common for her to show a lively, almost ill-tempered and irascible character [13]“.

Moreover, in addition to denying him the oedipian attachment that the young child demanded, his mother also forbade him the world of theatre: “My mother was concerned with not letting any inclination for theatre grow in me. […] She almost threatened me with her curse if I pretended to be interested in theatre.”These negative traits and the absence of maternal instinct are to be compared with a letter that Wagner wrote in September 1842 to Cäcilie; it refers to the lack of principles and whims of his mother, her fickleness, her tendency for the falsification of facts and fondness for gossip, her cupidity and selfishness [14]… But it is crucial to specify that age seems to have profoundly disturbed his mother’s character. Johanna would spend the rest of her life safe from material worries, thanks to her daughters and their rich marriages.

She died on 9 January, 1848, at the age of seventy-four. « She had spent the last years of her life, formerly so active and so unstable, in the serenity that comfort provides and, towards the end in a state of peaceful unconsciousness[15] » Wagner told us in his autobiography. He added, evoking his mother’s funeral: « I rushed to Leipzig for her funeral and I had the joy of being able to contemplate for the last time and with deep emotion the serene and peaceful face of the dead woman. […] We laid her in the grave on a cold morning. The clod of frozen soil that I took, according to custom, to throw it on the coffin, fell on the lid with a violent noise that frightened me. […] During the short journey from Leipzig to Dresden, I was clearly aware of the complete isolation I was in. The death of my mother had broken the natural ties between brothers and sisters absorbed by their personal interests[16]».

Richard’s relationship with his mother, probably very strong, was actually much more complex and marked with an extreme ambivalence. This is evidenced by a famous letter, written in Karlsbad on 25 July, 1835, that he addressed to her when she was sixty-one: « You are the only one, my dear mother, to whom I think with the most fervent love and the most profound emotion », then he added with suspicious excess: “I am undoubtedly one of those people who do not always know how to speak with their hearts in the moment, otherwise you would have quite often received the revelation from one side of my much tender nature. But feelings remain the same, and you see, Mother, now that I am away from you, I feel overwhelmed with gratitude for the magnificent love that you pour out on your child, and that you once again expressed recently with so much warmth and affection; It is so strong that I would like to write to you and say it with all the tenderness of a lover towards his beloved. What am I saying, it is so much more than that, isn’t the love of a mother indeed much more immaculate than any other?” The letter culminated in this sentence, in which he seemed to be wanting to be sure of his own feelings: “My dear, very dear mother, what a wretch I would be if my sentiment were to ever be cold towards you![17]“

To conclude, let’s find young Richard in his early years of childhood. He showed a strong tendency towards indiscipline, and displayed turbulent behaviour, unruliness, and an irascible character. The biographers asserted that he was an « enfant terrible », quick to be rowdy, but who arose the sympathy of all. Thanks to a letter of this time, it is learned that he hardly spent a day without tearing the bottom of his pants. It was said of him that he was a “noisy, a little brusque, almost violent[18]“. His stepfather liked to call him « the Cossack [19] » or « the little goblin ». The turbulent character is often attached by psychologists to a lack of internalised paternal image. In any case no sign that could indicate a child prodigy or a budding genius! The future would prove the opposite…

Excerpt from ![]() Pascal Boutedja “Richard Wagner’s parents”

Pascal Boutedja “Richard Wagner’s parents”

[1] Some sources incorrectly present the date of 1778.

[2] Other spellings exist: Bertz, Betz and Berthis.

[3] Richard Wagner, My Life, p. 19

[4] See:« The prince Constantin question », in : Ernest Newman, The Life of Richard Wagner. II. 1848-1860, pp.613-619.

[5] Martin Gregor-Dellin, Richard Wagner. Paris, Fayard, 1981, p.40.

[6] Martin Gregor-Dellin, Recent search results on Wagner. Bayreuther Festspiele Programm

Parsifal, 1985, pp. 81-90.

[7] Wagner’s mother never told her children the name of the « institution » of Leipzig, where she would have been brought up… and for good reason!

[8] Martin Gregor-Dellin, Recent search results on Wagner, p.87.

[9] Ibid, p.87

[10] Joachim Kôhler, Richard Wagner. The Last of the Titans. London, Yale University Press, 2004, p.9.

[11] Mary Burell Richard Wagner. His Life and Works from 1813 to 1834, p. 16.

[12]« Meine Mutter – ein Menschenweib ! » (Siegfried, Acte II, scène 2).

[13] Richard Wagner, My Life, pp. 19-20.

[14] Richard Wagner, My Life, pp. 19-20.

[15] Sämtliche Briefe. Band II, pp. 155-160.

[16] Richard Wagner, My Life, p. 236

[17] Richard Wagner, My Life, pp. 209-213.

[18] Sämtliche Briefe. Band I., p. 148.

[19] Herbert Barth, Wagner. A documentary study, p. 148.

If you wish to share further information about this article, please feel free to contact us !