If Wagner was the cultural and musical chronicler of his time, if he remained a revolutionary activist, he had also gone into the act of police, and if he was finally his master of Bayreuth celebrated as the one of the major artist of his At the time, the illustrious composer did not live before a man made of chair and blood, animated by passions, with a sometimes violent, sometimes facetious, and sometimes tender character.

THOSE RELATED ARTICLES MAY

INTEREST YOU

YEAR 1883

YEAR 1883

During the first days of 1883, Richard Wagner learned the invention of the phonograph, this news the unworthy as it saddened. February 6, 1883 (Mardi Gras Evening) The Carnival is in full swing and the Wagners are St. Mark’s Square where they see the procession of Prince Carnival (Read More)

ELEGY WWV93

ELEGY WWV93

This fragmentary work (album sheet) in A flat major seems to have been written by Wagner in 1869. This page was long considered a late work (see the last notes he drew in Venice before his death in 1883). Wagner played it said the day before his death. (Read more)

TRISTAN AND ISOLDE

TRISTAN AND ISOLDE

Richard Wagner’s seventh opera, Tristan and Isolde (WWV 90) is the fourth in the so-called period of maturity of the composer and the first created under the patronage of King Ludwig II of Bavaria. It is also the only work resulting from an order in the career of the composer: March 9, 1857, (Read more)

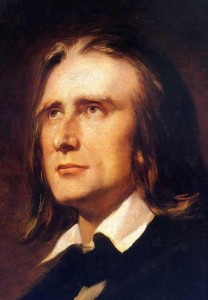

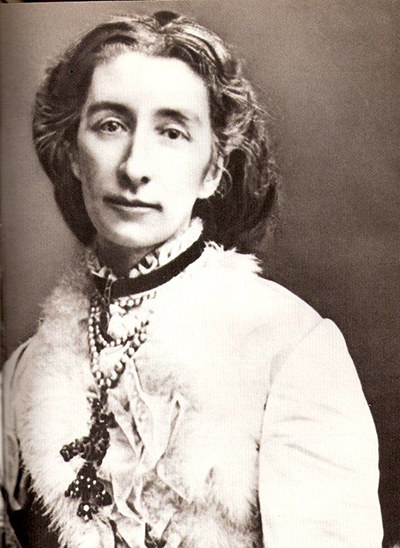

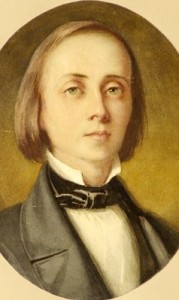

von BÜLOW WAGNER (born LISZT) Cosima

(born on 24 December, 1837 – died on 1 April, 1930)

Daughter of Franz (Ferenc) Liszt and Marie d’Agout ;

Second wife of Richard Wagner

Cosima’s story could be summarized or rather recognized in each of her names. Cosima born Liszt, Cosima married to von Bülow, Cosima married to Wagner, Cosima widow of Wagner: one could write a biography about each of them and the portraits would not look the same. In turn, she was the daughter of one of the most famous and brilliant musicians (but also one of the biggest womanisers) of his time, the wife of a studious (but touchy) conductor who admired the undoubtedly most charismatic composer of his entourage, mistress then wife and finally widow of this same composer, Richard Wagner. The mother of the children that Minna could not have given him in his first marriage, Cosima was, beside the one that even as a child she already revered as a god, the most devoted wife, but also one of the strongest pillars of Wagnerism… to the point of adopting an absolute rigour in the admiration she had for Richard Wagner’s art, which was disconcerting!

Illegitimate siblings

Born in Como, Cosima Francesca Gaetana is the illegitimate daughter of Marie d’Agoult (Marie Catherine Sophie de Flavigny, Comtesse d’Agoult), a French woman of letters known by her pen name Daniel Stern, particularly lively and brilliant, and Franz Liszt, famous composer and virtuoso pianist, six years younger than her. Contrary to what has sometimes been written, the name Cosima was not chosen because she was born near Lake Como, but in honour of Saint Cosmas, patron saint of doctors and pharmacists, that we celebrate on 26 December, the day Cosima received the sacrament of baptism.

The complexity that surrounded Cosima’s birth may explain some of her character traits.

Her mother, Marie, was the daughter of Alexandre Victor Francis de Flavigny, a French Catholic noble and Maria Elisabeth Bethmann, born of an old German Protestant patrician family. Raised between France and Germany, between Catholicism and Protestantism, she had two daughters with her husband, the Comte d’Agoult: Louise and Claire (who married the Marquis de Charnacé). It was the death of her eldest daughter Louise that persuaded Marie to give up everything to escape with her lover Franz Liszt. Their relationship, passionate, complicated, made of splits and reconciliations, was summarized by George Sand with the expression “galley slaves of love”.

Liszt and Marie d’Agoult (nicknamed Arabella) had three children: Blandine, called “Mouche“, future wife of Emile Ollivier, Cosima and Daniel who died at twenty.

Liszt and Marie d’Agoult (nicknamed Arabella) had three children: Blandine, called “Mouche“, future wife of Emile Ollivier, Cosima and Daniel who died at twenty.

The affair that united Marie d’Agoult and Franz Liszt deteriorated rather quickly and agonized for a long time. When they separated in April 1844, Liszt entrusted their children to his own mother’s care, Mrs. Anna, a former chambermaid in Vienna, and forbade Marie to see them. The Flavignys, meanwhile, never wanted to hear about this illegitimate progeny and Marie did not participate financially in the caretaking of the children.

In this somewhat chaotic childhood, Cosima gave all her love to her sister and her younger brother, and also had a strong love for this father that she hardly ever saw, when she almost devoted hatred to this mother who had no right to intervene in their education. Liszt, moreover, as seducer in society as he was a brilliant musician, did not deprive himself of multiplying the romantic conquests.

A relationship between the father and the daughter that became even more complicated when Carolyne von Sayn-Wittgenstein entered Liszt’s life.

Wanting to erase all possible influence of Marie d’Agoult, she decided first to remove the children from the affectionate solicitude of their grandmother to entrust them to a severe governess (Madame de Patersi de Fossombroni), from 1850 to 1855. Under her particularly rigid influence combined with the education provided by the Abbe Gabriel, the two sisters learned and came to terms with the idea that “the entire life [of a woman] must only serve as a sacrifice, and that she must only be a living host”. The notions of martyrdom, sacrifice and duty settled from then on in Cosima’s life.

In autumn 1853, for the first time in nine years, Liszt’s children finally saw their father again. Liszt received Wagner “at” his daughters’, who thus went from the most absolute isolation and rigour to the most brilliant society. Cosima, distraught, did not look up during the whole evening.

But always jealous of the slightest possible relationship between Marie d’Agoult and her daughters, the princess decided in September 1855 to send the girls to Berlin under the care of Franziska von Bülow, Hans’s mother, Cosima’s future husband.

The young Cosima who carried several cultures in her, herself a living mirror reflecting only too well the conflicts of her ancestors, locked herself into the most extreme shyness that painstakingly hid the tears of her beautiful romantic soul.

A marriage of convenience

A marriage of convenience

Cosima married Hans von Bülow, a young conductor, composer, a pupil of her father and already a loyal Wagnerian at the age of nineteen, in 1857. Why did she marry him? She did not love him and it was indeed a marriage of convenience. Their engagements, however, were very romantic: on 19 October, 1855, so six weeks after Cosima and Blandine’s arrival in Berlin, Hans von Bülow had to direct during a concert the overture to Tannhaüser. Already the shadow of the giant Wagner was floating above the couple…

During this particularly gruelling concert for the young conductor, booed and whistled by the public, he retreated into his dressing room, stricken with a fit of hysterics. Having entered with Franzisca von Bülow, Cosima waited for the young master till he returned, and spent the rest of the night comforting him. And it was in this context that the engagement happened.

At the news of this future union, Franz Liszt, at first cautious, finally gave his blessing: Hans, whom he already regarded as his spiritual son, was to become his son-in-law. Satisfied with his younger daughter’s wisdom, he showed her the affection she needed so badly. On the contrary, irritated by Blandine’s strength of character, who had decided to return to Paris, he remained for a long time very cold towards her. (NB: Their relationship did not improve until her marriage with Emile Ollivier. However, she did not have a better relationship with her mother than Cosima).

As for Hans, he was not known for being a delicate individual. Subject to health problems that made him nervous, he hurt Cosima’s sensitivity. But this latter (the duty, always the duty) did not bat an eye. After having just got married, and while they had to go on a honeymoon, von Bülow and his young bride found themselves at the Wesendoncks’, since Wagner needed the young conductor, and when Wagner called him, von Bülow came. A particularly singular and classic scene was to take place: Wagner declaimed the verses of the poem of his future Tristan and Isolde, von Bülow was at the piano. Around this exceptional duo, three women: Minna, dazed by the effects of the laudanum, was absent in spirit from what could be going on, Mathilde Wesendonck looked at her poet with the fever of ecstasy in her eyes, and, Cosima, in a corner of the room was crying… And yet… If we add to this picture the presence of a first husband being cheated on (Otto Wesendonck), there could not be a more emblematic scene of the love and complicated relationships these beings would maintain for the nearly twenty years that would follow!

In addition to this disappointing marriage, already placed under Wagner’s shadow, Cosima lost the two people that mattered the most to her: her younger brother Daniel, who died in 1859, and her sister Blandine, who died in 1862. In their memory, she named her daughter born in 1860 Daniela, and the one born in 1863 Blandine. No really, this first marriage with von Bülow was not born under a lucky star.

During all the years spent with Hans von Bülow, Cosima observed. She observed Wagner to whom she already vowed a great admiration, even though he at first only saw her as a child, a very (maybe too much ?) reserved child. She witnessed the composer’s love stories, she witnessed the difficulties of his first marriage.

Little by little their feelings evolved. Cosima, married and mother of two children, and Wagner, twenty-four years older than her, also married, confessed their feelings for each other, in tears. It was the beginning of an affair that would be extensively talked about…

A sinful affair, a woman bruised by the weight of guilt and public condemnation

A sinful affair, a woman bruised by the weight of guilt and public condemnation

For several years, the couple tried to keep up appearances and denied the obvious, with the help of the deceived husband. Indeed, this romantic relationship was particularly complicated. Besides the stakes for Cosima, that polite society could only reject, she called many relationships into question:

– Thus, Cosima and Hans: the couple pretended for several years to still get along. Hans von Bülow thus assumed the paternity of the two illegitimate daughters that Cosima had with Richard Wagner. He even tried to use Daniela and Blandine, whom he kept close to him, to make Cosima come back.

– Wagner and Hans: the composer continued to see von Bülow as a devoted conductor, and the fact is, the neglected husband remained loyal to Wagner. He even said to Cosima “I forgive you”, to which she replied “It is not necessary to forgive, it is necessary to understand”.

– Cosima and Liszt: for several years, Liszt cut all ties with his daughter. He did not forgive her for having deserted her home. The relationship did not improve the day Cosima converted to Protestantism; Abbe Liszt retained some bitterness. During all these years of silence, it was from Daniela, his favourite granddaughter, that Liszt caught up on Cosima’s news.

– Liszt and Wagner: if Liszt knew how to separate Wagner as a man from him as a composer, it was not the same for Wagner, who criticized him a lot and quite violently to Cosima, who wept a lot because of it. This was perhaps the greatest point of contention in the couple.

– Ludwig II: the King of (catholic) Bavaria, when told of the rumours about Wagner and Cosima von Bülow, asked for an explanation and believed the outraged denials of the composer and the faithful wife of the conductor von Bülow. Their denials, their plea of innocence, singularly complicated the relationship between the artist and the patron.

While Ludwig II provided Wagner with a first provisional dwelling on Lake Starnberg (Villa Pellet), von Bülow was offered a position as “royal pianist”. Thus the pianist and his wife Cosima lived in Munich, in a house neighboring Wagner’s. Appearances were kept up and Cosima could officially work as the composer’s secretary.

While Ludwig II provided Wagner with a first provisional dwelling on Lake Starnberg (Villa Pellet), von Bülow was offered a position as “royal pianist”. Thus the pianist and his wife Cosima lived in Munich, in a house neighboring Wagner’s. Appearances were kept up and Cosima could officially work as the composer’s secretary.

In June 1864 Cosima spent more than a week alone with Wagner at Lake Starnberg, before von Bülow joined them. According to Wagner’s governess, Anna Mrazek, “it was easy to say that something was going on between Frau Cosima and Richard Wagner”.

Nine months after this visit, on 10 April, 1865, Cosima gave birth to a daughter, Isolde, that von Bülow claimed. On 10 June, 1865, two months after her birth, von Bülow conducted the Premiere of Tristan and Isolde in Munich.

Wagner’s position in the court of Ludwig II soon became difficult. His political recommendations, his ever more pressing demands regarding the construction of a Festtheater specially dedicated to the creation of his works, his flashy tastes in terms of “art de vivre” that he did not hide in the least from the public’s eye, tired the Bavarian government. In December 1865, the King reluctantly had to make Wagner leave Bavaria. After a few months, in March 1866, Wagner arrived in Geneva, where Cosima joined him. They travelled together to Lucerne and found a large house along the lake of the Four Forested Settlements, in Tribschen.

Immediately, Wagner invited the von Bülows and their children. After the summer, Hans von Bülow left for Basel while Cosima stayed in Tribschen. Wagner, anxious to spare Cosima from a public scandal, asked Ludwig II to silence the “gossip” with a declaration in June 1866 that certified Cosima’s innocence.

Immediately, Wagner invited the von Bülows and their children. After the summer, Hans von Bülow left for Basel while Cosima stayed in Tribschen. Wagner, anxious to spare Cosima from a public scandal, asked Ludwig II to silence the “gossip” with a declaration in June 1866 that certified Cosima’s innocence.

At this moment, Cosima was expecting another child with Wagner; it was a girl, Eva, who was born in Tribschen on 17 February, 1867. Meanwhile, Hans von Bülow was preparing the Premiere of the Master-Singers that took place on 21 June, 1868 and had, more than just a success, a worldwide impact!

In October 1868 Cosima asked her husband for a divorce, which he refused. But in June 1869, immediately after the birth of her third and last child with Wagner, Siegfried, Cosima wrote to von Bülow and this time obtained his agreement for a divorce. Since poor Minna had died in 1865, Richard and Cosima were able to marry in Lucerne on 25 August, 1870, in a Protestant church.

On 25. December, the day Cosima celebrated her birthday even though she was born on the 24th, she woke up to the sound of music. Richard had indeed set up his orchestra on the stairs, and played what became known as the Siegfried Idyll.

Cosima, a devoted mother and wife

Cosima, a devoted mother and wife

Mistress, wife, mother, secretary, nurse: there was nothing that Cosima did not do for the God Richard Wagner, her God. Accompanying loyally her great love, she gave the image of an unfailing strength. After much patience to endure the reversals of fortune, the composer’s failures and frustrations, she then witnessed, overjoyed, her husband’s triumphs.

Her famous Diary, that she kept from 1869 to 1883, traced all the events in the couple’s life, from insignificant ones (i.e. Richard’s sleep or the food which was given to the home’s pets) to the most fascinating (concerning the first festival in Bayreuth for instance).

Cosima maintained a rich correspondence with the most illustrious figures who had socialized with Wagner: with King Ludwig II of course, Friedrich Nietzsche, who apparently had feelings for the hostess of Tribschen, Judith Gautier, Gottfried Semper, Arthur de Gobineau and many others…

She thus tried to coax King Ludwig II to persuade him to help her husband. Indeed, the king had been offended by Wagner’s lies regarding his relationship with Cosima. Moreover, he was waiting impatiently for the delivery of the last two operas of The Ring. These ones being late to arrive, Ludwig II decided that the premieres of the two operas The Rhinegold and The Valkyrie would be performed in Munich. They took place on 22 September, 1869, and on 26 June, 1870 respectively, which offended Wagner.

It was this event that decided the history of Bayreuth, Wagner looking for a place where he could have his Ring performed under the conditions he wanted.

It was the end of the idyll in Tribschen, and the beginning of the “Wahnfried” story, the villa in which Wagner, Cosima and the children moved in on 18 April, 1874. Commenting on the struggle to finish the Festspielhaus building , Wagner said to Cosima: “Each stone is red with my blood and yours“.

Cosima, the guardian of the temple

Cosima, the guardian of the temple

When Richard Wagner died in Venice on 13 February, 1883, Cosima, grief-stricken, would not let go of the corpse. She laid down beside him, mute, as she did on the coffin, on the day of Wagner’s funeral at Villa Wahnfried. The widow locked herself into her mourning. It took her several months to agree to get out of her isolation.

Cosima nevertheless survived Richard by forty-seven years. During this time – that she herself had not considered – she devoted herself exclusively to the defence of her husband’s work. Indeed, she knew how to successfully complete the composer’s initial intention, namely to create a lasting, regular festival, allowing for the execution of the Wagnerian musical dramas. She went so far as to meet with strong resistance when she dared to produce on the Bayreuth stage the dramas Tristan, The Master-Singers, Tannhaüser and finally Lohengrin on a stage that had only seen The Ring and Parsifal. With successes as well as failures: with such courage, investment to persist in her work when, at the worst of this wave, Tristanwas performed in front of just two hundred spectators.

Her unfailing loyalty to her husband’s work for that matter transformed Bayreuth, initially a temple of novelty, into a mausoleum. She wrote to Hermann Levi: “We should banish any realistic element, of a conventional and banal nature, in favour of a superior convention, which is style”. From then on, she banned all spontaneous expressions of artists, halted and froze the game, turning Bayreuth into a mausoleum and stopping time.

Her children had to, themselves, measure up to their heritage. Their spiritual heritage, that is, since the material inheritance was destined for Siegfried, the only one to bear Wagner’s name. Cosima undoubtedly loved her children, but she poured out her feelings of guilt on them. She stifled her daughters, and asked them to step aside in favour of the son, Siegfried, who himself had a hard time asserting his independence! It was impossible for him to take a step out of the ready-made path. Isolde had the bad idea of marrying a Swiss conductor, Franz Beidler. He was expelled from Bayreuth by Cosima, who feared competition for her son Siegfried. Furious, Isolde then demanded her share of the inheritance. Cosima went to trial to deny her the Wagnerian ancestry. She is a von Bülow! Isolde lost her paternity trial and died of tuberculosis in 1919, abandoned by her family and husband.

But this iron grip that stifled her descendants was certainly what allowed for the matriarch to take the reins of Bayreuth. And this was done painfully; she was of French origin and a woman: two major obstacles to her recognition.

The “Guardians of the Grail,” the Wagnerians, opposed with all their might to this succession. Liszt or Bülow would have been more to their taste. But Cosima prevailed. To save Bayreuth, she exerted all her energy. But her error consisted in believing that to impose the works of the deceased, the only way was fixity, embalming. She imposed a unique staging and singing style.

If Cosima left the reins of the Festival to her son Siegfried in 1908, she only died in 1930 at the age of ninety-two; Siegfried, himself, died a few months later. A new era was about to start for a Festival which would henceforth be placed under the protection – and the artistic direction – of the Third Reich…

SB.

If you wish to share further information about this article, please feel free to contact us !