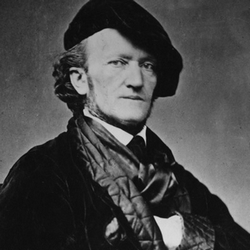

Wagner, the first European composer! If the name of the composer sounds more German than the noun “Germany”, the artist, himself always in search of notoriety and success that he could not find within the borders of the German Empire, exiled in his younger years to find recognition… elsewhere. And these new horizons, Wagner would seek them from London to Saint Petersburg, passing by Paris, Venice or Zurich, places that were as much living places as places of musical creation and artistic inspiration.

London

Less famous and less disastrous than the Parisian episodes, but still disappointing, Richard Wagner made some trips to London with the same goal as Paris: to conquer the foreign public!

Back to Richard Wagner’s three London trips and his attempts to get his “Music of the Future” accepted outside the borders of Germany.

First trip (1839)

First trip (1839)

Before attempting to obtain from the great Giacomo Meyerbeer a recommendation to promote the production of his new works on one of the Parisian lyrical stages, Wagner made his first stop in London. Totally unknown, miserable and fleeing his creditors, with his wife Minna and the faithful (but a little cumbersome) Robber (a Newfoundland!), our composer first set foot on British soil on 12 August, 1839. The couple and the dog found “asylum” in a boarding house in Soho, on the Great Compton Street.

The composer’s aim in going to London was first and foremost to meet the famous writer Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1803-1873), author of Rienzi, Last of the Roman Tribunes, a work on which Wagner had worked in order to compose a new opera. On his arrival, and knowing that Baron Bulwer-Lytton sat in the Chamber of Peers, Wagner went to Parliament. Unfortunately, the writer was not in town: the rendezvous between the man of letters and the man of music was thus missed. It was, however, an opportunity for our intrepid and curious composer to visit Parliament and to attend one of its sessions. Neither the Prime Minister at the time, Lord Melbourne, nor the famous Duke of Wellington left a lasting or particularly favourable impression on the composer.

The composer’s aim in going to London was first and foremost to meet the famous writer Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1803-1873), author of Rienzi, Last of the Roman Tribunes, a work on which Wagner had worked in order to compose a new opera. On his arrival, and knowing that Baron Bulwer-Lytton sat in the Chamber of Peers, Wagner went to Parliament. Unfortunately, the writer was not in town: the rendezvous between the man of letters and the man of music was thus missed. It was, however, an opportunity for our intrepid and curious composer to visit Parliament and to attend one of its sessions. Neither the Prime Minister at the time, Lord Melbourne, nor the famous Duke of Wellington left a lasting or particularly favourable impression on the composer.

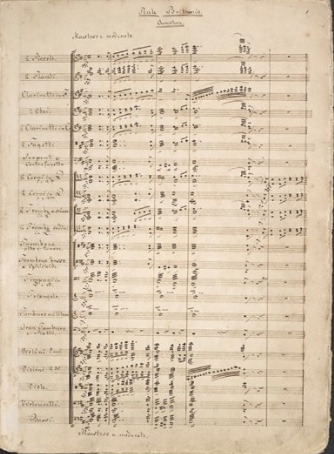

Another concern of Wagner: to know what had become of the manuscript of his Overture Rule Britannia, an early work based on the melody of the English National Anthem and sent many years before to Sir John Smart, President of the London Philharmonic Society. Without having received any feedback! What if, taking advantage of his stay there, he could at least get his hands on his manuscript? New disappointment, Sir John Smart did not live in the capital.

These London walks left to the couple “an unforgettable impression of desert” (Mein Leben) while embarking for Paris. Wagner’s first trip to London thus ended on August 20, 1839, on a bitter impression. But it did not matter, it was the hoped-for success in Paris that guided the couple.

Second trip (1855)

Second trip (1855)

It took a little more than fifteen years for Wagner to attempt a new onslaught on the Victorian megalopolis. At the invitation of the Philharmonic Society, the composer – then in exile in Zurich – went to London on 26 February, 1855 to conduct a series of concerts in London. Arriving on 2 March, Wagner moved in a dwelling in Portland Terrace, on Regent’s Park, much more decent and comfortable than the boarding house, refuge of his first stay in 1839. The fee proposed to the composer for the occasion by the venerable institution was considerable: 200 books for the direction of eight concerts. Annoyed by the climate, (but what could be expected of London in the middle of winter?!“It seemed to me that this spring would never happen, since the misty climate weighed on me so much” wrote the composer later in Mein Leben), he expected a lot from the orchestra.

In the repertoire of the Old Philharmonic Society, one of the most prestigious orchestras in Europe in the mid-19th century, there were almost only works by Handel or Mendelssohn, composers revered as absolute masters. In search of notoriety, eager to “make a name” for himself, and disappointed with the Zurich formation that he directed, it was the reputation of the musicians of the Orchestra that attracted him, more than the repertoire of the formation: no amateur musicians, so many talented quasi-soloists at each pulpit. “You’re the famous Philharmonic Orchestra,” he shouted during the first rehearsal. “Raise yourselves, gentlemen, be artists!”

In this environment conducive to excellence, the composer was undoubtedly expecting much more than the one rehearsal per concert: it was not that, and it was indeed the “strict minimum” imposed by the management of the institution that Wagner had to make do with!

In this environment conducive to excellence, the composer was undoubtedly expecting much more than the one rehearsal per concert: it was not that, and it was indeed the “strict minimum” imposed by the management of the institution that Wagner had to make do with!

To make matters worse, our intrepid musical adventurer marked again his contempt for customs and neglected the interviews that had been arranged for him with the principal figures of the local critics of the moment. James Davison, then a popular critic of the Times and editor of the highly influential Musical World, was part of this crowd that was seen negatively by Wagner. It took Wagner a long time to understand that assuming the cause of the media was an essential and necessary task for any enterprise aiming at popularity.

From 12 March to 25 June, Wagner directed a series of eight concerts including obviously works by Handel and Mendelssohn, but also by Mozart, Beethoven, Weber, Spohr, Cherubini and some of his own compositions (excerpts from Lohengrin as well as the Overture to Tannhäuser, only concessions made to the composer to “perform”).

From 12 March to 25 June, Wagner directed a series of eight concerts including obviously works by Handel and Mendelssohn, but also by Mozart, Beethoven, Weber, Spohr, Cherubini and some of his own compositions (excerpts from Lohengrin as well as the Overture to Tannhäuser, only concessions made to the composer to “perform”).

From the first concert, the press united strongly behind Davison and opposed to the composer a reaction and very negative criticisms. Wagner was deeply disappointed and affected by it. Tired of the venerable but ancestral customs of the orchestra (for example, he loathed the discomfort of having to steer it with white gloves), disappointed with the demands that remained unanswered to obtain the right to enjoy more rehearsals, Wagner withdrew into himself (with the contempt and the – bad – but whole character that we know him for) and continued each night (undoubtedly with even more rage and determination) the composition of his own works. That is how, on 3 April, 1855, the composer completed the original manuscript of the score of Act I of The Valkyrie (Die Walküre). Nevertheless, and in spite of the fierce opposition of an unanimous press to stand in the way of the composer’s success, Wagner succeeded little by little in winning the support of his public. The fifth concert was even a great success: the audience gave an ovation to the conductor and, according to custom, the spectators rose, waving their handkerchiefs as a sign of sympathy.

The seventh concert (11 June, 1855), attended by Queen Victoria in person, was an event: the sovereign having heard the success of the Overture to Tannhäuser given during a previous concert, asked that the work (that was initially not planned in this evening’s program) be included. At the end of the concert, the Queen asked to meet the composer and congratulated him for the composition “that had captivated her.” Finally, and despite the relentless attempts of a press willing to do anything to silence the success of the conductor-composer, the last concert (on 25 June) ended with a never-ending ovation from the public and a farewell banquet was organized.

The seventh concert (11 June, 1855), attended by Queen Victoria in person, was an event: the sovereign having heard the success of the Overture to Tannhäuser given during a previous concert, asked that the work (that was initially not planned in this evening’s program) be included. At the end of the concert, the Queen asked to meet the composer and congratulated him for the composition “that had captivated her.” Finally, and despite the relentless attempts of a press willing to do anything to silence the success of the conductor-composer, the last concert (on 25 June) ended with a never-ending ovation from the public and a farewell banquet was organized.

Although generally disappointed by the welcome he had received during his stay, Wagner returned to Switzerland with the satisfaction of having been able to win a battle: that of Queen Victoria’s heart!

With his tendency to take shortcuts, the composer was quickly convinced that the French and the English people were desperately foreign to any concept of “Music of the Future“: too mired in their habits, and foreign to any form of modernity, it would have been a loss of time to attempt to rally to his cause a people whose opinion was held by the opinion of the press.

Third and last trip (1877)

Third and last trip (1877)

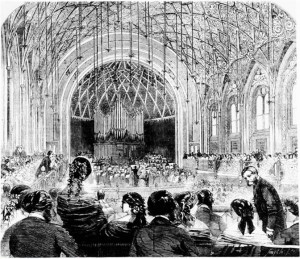

It was not until 1877 that, in his attempt to refill the coffers of the first edition of the Bayreuth Festival (a real financial abyss), that Wagner decided for the third time to take on England. Between 7 and 29 May, 1877 Wagner, together with conductor Hans Richter, directed a series of eight concerts at Albert Hall in London; in their programs were included, among others, excerpts from The Flying Dutchman (Der Fliegende Holländer) and The Valkyrie (Die Walküre).

It was during this stay that the composer and his new wife, Cosima, were received by Queen Victoria at the Windsor Castle. In the evening, and before a small circle of friends, Wagner read the poem of Parsifal.

At the end of his third and last stay in the British capital, the composer returned with a net receipt of 700 pounds sterling, i.e. one tenth of the Bayreuth deficit.

The relationship Richard Wagner had with England could be summed up, even more than the admiration that the all-powerful sovereign Victoria felt for the composer’s work, as her personality and destiny: a sensitive personality, smitten and open to any form of modernity, but which had, by its rank and facing a society codified to the extreme, to reign with an iron fist and to make do as much as he could with the ceremonial, preconceived ideas and the strength of traditions.

Outside of their respective contexts, the Queen and the composer would probably have enjoyed the development of a strong intellectual relationship and the Sovereign would undoubtedly have been able to further the success of one of her favourite composers. But to do so, it would have been necessary for the latter to pay more attention to etiquette and respect traditions. And we know that our dear Richard Wagner was far from lending himself to this type of concession!

NC.

If you wish to share further information about this article, please feel free to contact us !