VI. THE POST-WAR YEARS

VI. THE POST-WAR YEARS

AND THE “NEUE BAYREUTH” (NEW BAYREUTH)

The image of the Third Reich was, at the end of the war, strongly associated with Bayreuth, even with Wagner’s work itself, whose initial scope Nazism lead astray.

And the management of the Festival in the person of Winifred had shown its personal sympathies too much for the cult of Wagner and his works to be permitted at the Festspielhaus under occupation of the Allied forces from 1945 onwards.

Richard Wagner, Winifred, Bayreuth and his Festival, Hitler, the Third Reich: all of that felt off in the small Franconian province that did not suspect a few decades earlier that it would become as much a place for art as a place where the most subversive politics of history would be located.

During the years of American occupation, attempts were therefore made to banish the god Wagner from his temple and the works of the composer were tacitly forbidden. A temporary artistic direction under the auspices of the “new occupation“, in this case American, transformed the temple dedicated to the Wagnerian cult into a scene of music-hall revues, where Broadway musicals were performed such as Italian or French opera works. It was not until 1951 that Winifred, deprived of her rights by a military court in 1949, entrusted the direction of the festival to her two sons, Wolfgang and Wieland, the innovative and visionary director.

1 – The “Neue Bayreuth” (« New Bayreuth »)

It took until 1951 for what was called the “new Bayreuth” – or “renewal of the Bayreuth Festival“-, in German “Das Neue Bayreuth” to re-open. With this expression, one must understand that it was an openly “denazified” Bayreuth that, on the one hand, had again the right to exist without any shame or justification and, on the other hand, an openly innovative and revolutionary festival regarding opera performances. No more winged helmets, armour and heaumes that Cosima kept by blind tradition to her deceased husband, from then on was the time for Wieland Wagner’s refined and minimalist stage productions. From the first edition of this renewal, the genius of the artistic director was expressed through productions inspired by the precepts of Adolphe Appia all while betting (the tradition remained on this point) on the best singers as well as the most talented conductors.

It took until 1951 for what was called the “new Bayreuth” – or “renewal of the Bayreuth Festival“-, in German “Das Neue Bayreuth” to re-open. With this expression, one must understand that it was an openly “denazified” Bayreuth that, on the one hand, had again the right to exist without any shame or justification and, on the other hand, an openly innovative and revolutionary festival regarding opera performances. No more winged helmets, armour and heaumes that Cosima kept by blind tradition to her deceased husband, from then on was the time for Wieland Wagner’s refined and minimalist stage productions. From the first edition of this renewal, the genius of the artistic director was expressed through productions inspired by the precepts of Adolphe Appia all while betting (the tradition remained on this point) on the best singers as well as the most talented conductors.

And, as a warning sign, in the immediate vicinity of the Festspielhaus, a poster made clear what it was about: “Hier gilt’s der Kunst !” (Art reigns here). No ambiguity was therefore allowed as for the intentions of the new team led by the two grandsons of the composer, Wieland leading the way. Henceforth, in Bayreuth, politics or ideology were no longer talked about: only Art reigned supreme.

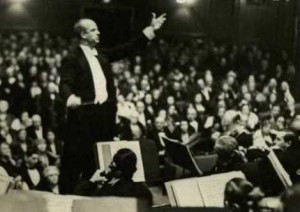

For the official opening of the Festival, which took place on 29 July, 1951, Wilhelm Furtwängler (who already had the opportunity to publicly explain his opposition to the Nazi regime – an additional selling point by Wieland to convince the public and the press) directed the Ludwig van Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, a work dear to Richard Wagner and the only non Wagnerian work to be staged in the tradition of the History of the Bayreuth Festival (it was reprised afterwards on a few occasions, notably in 1953 and 1963).

For the official opening of the Festival, which took place on 29 July, 1951, Wilhelm Furtwängler (who already had the opportunity to publicly explain his opposition to the Nazi regime – an additional selling point by Wieland to convince the public and the press) directed the Ludwig van Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, a work dear to Richard Wagner and the only non Wagnerian work to be staged in the tradition of the History of the Bayreuth Festival (it was reprised afterwards on a few occasions, notably in 1953 and 1963).

Wieland’s choice was in itself a real homage to the purest and most faithful Wagnerian tradition, this work having been staged at The Margravial Opera House on 22 May, 1872 while the composer, grandfather of Wieland, also celebrated with exuberance laying the foundation stone of the construction site of the Festival Theatre.

The distributions bringing together the best singers of the moment (Hans Hotter, Ludwig Weber, Wolfgang Windgassen, George London, Ramon Vinay, Gustav Neidlinger, Martha Mödl, Regina Resnik, Astrid Varnay, Birgit Nilsson) drew the public which made the move despite the audacious productions of the composer’s grandson.

The distributions bringing together the best singers of the moment (Hans Hotter, Ludwig Weber, Wolfgang Windgassen, George London, Ramon Vinay, Gustav Neidlinger, Martha Mödl, Regina Resnik, Astrid Varnay, Birgit Nilsson) drew the public which made the move despite the audacious productions of the composer’s grandson.

In this new golden age of Wagnerian singing, Bayreuth quickly rebuilt a reputation for excellence and became once again a prized place for all critics and the international elite, and synonymous with a renewal in the lyric art of the 20.th century. The seats for the festival started being exchanged at premium prices.

2 – Wieland Wagner’s art revealed to the public of the “New Bayreuth”

Minimalist, symbolic, playing with the depth of the stage and the subtle lighting, the stage productions by Wieland Wagner that highlighted the universal and timeless scope of the works did not take long to become legendary. All of Wieland Wagner’s productions remained in a state of constant evolution.

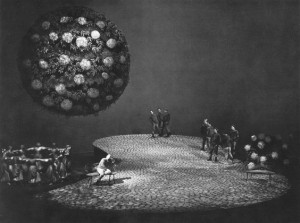

From 1951 to 1966, it was a progression, like an initiation rite of abstraction towards the most total destitution. Presumably due to time constraints and despite his desire to “hit the old men of Munich over the head”, to use one of his expressions, Wieland did not give all of his art in 1951; he offered over the years to an audience increasingly fan of this progression towards total purification, a true initiatory journey. Thus, if in 1951 Siegfried had to fight with a sword in his hands a cardboard Fafner dragon, the great director only showed at the end of his Ring a projection which was itself gradually removed.

From 1951 to 1966, it was a progression, like an initiation rite of abstraction towards the most total destitution. Presumably due to time constraints and despite his desire to “hit the old men of Munich over the head”, to use one of his expressions, Wieland did not give all of his art in 1951; he offered over the years to an audience increasingly fan of this progression towards total purification, a true initiatory journey. Thus, if in 1951 Siegfried had to fight with a sword in his hands a cardboard Fafner dragon, the great director only showed at the end of his Ring a projection which was itself gradually removed.

The stage productions of the Festival of 1951 were thus between figurative art and abstract art: many of the paintings of these two productions were realized not on the basis of a given sketch, but from simple sketches or functional diagrams and the sets were suggested on a plateau stripped to the extreme and simply dressed with spotlights.

Let us take a particularly significant example of this progression of Richard’s work in Wieland’s performances: Parsifal as it was presented in 1951 and then constantly reworked until the director’s death in 1966.

The first act in which could be seen in the olden days (and in accordance with the libretto), a thick forest and, below, the lake where Amfortas, the wounded King, bathed, only presented from then on shadows of trees projected on the cyclorama by rays of light falling from spotlights placed in the hangers and thus giving the impression of rays of sunshine through an (imaginary) forest of pines.

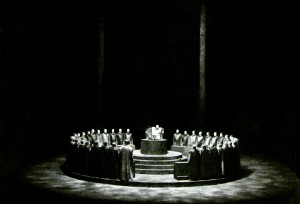

At the center of the stage, a circular platform formed the center of the action, which, after a brief precipitate and a short period during which the curtain was down, became the base of the altar of the Brotherhood of the Grail. If the temple in 1951 was generally similar in its construction to that of 1882, it too became over the years increasingly abstract: a few columns, then a few rays of light suggesting these same columns, were sufficient to delimit the Hall of the Grail premises.

At the center of the stage, a circular platform formed the center of the action, which, after a brief precipitate and a short period during which the curtain was down, became the base of the altar of the Brotherhood of the Grail. If the temple in 1951 was generally similar in its construction to that of 1882, it too became over the years increasingly abstract: a few columns, then a few rays of light suggesting these same columns, were sufficient to delimit the Hall of the Grail premises.

The role of the light, according to Appia’s theories, therefore became really preponderant. Klingsor’s cabinet, formerly bric-a-brac more in keeping with that of Dr. Jekill than a wizard’s laboratory, was from then on suggested by a kind of greenish cobweb (symbolizing the psychological meanders and perdition of the fallen Knight) from which emerged successively the mage then his damned soul, Kundry.

No more Gurnemanz retreat in the third act either, but an almost empty plateau reflecting the despair of a brotherhood deprived of its King; the traditional fountain in which Kundry, penitent Mary Magdalene, washed Parsifal’s feet before drying them with his hair was materialized by a stone pond of rectangular shape with a simple bench; the most extreme nudity to mean the most total destitution.

No more Gurnemanz retreat in the third act either, but an almost empty plateau reflecting the despair of a brotherhood deprived of its King; the traditional fountain in which Kundry, penitent Mary Magdalene, washed Parsifal’s feet before drying them with his hair was materialized by a stone pond of rectangular shape with a simple bench; the most extreme nudity to mean the most total destitution.

As for the dove that could be seen descending from the hangers in the last painting and placing itself on Parsifal’s head, it was from then on symbolized by a single beam of light.

Wieland Wagner’s revolution in his overall staging aesthetic also necessarily concerned the costumes and the psychological approach of the characters. Already the choruses: Richard Wagner initially did not want the choirs to play because, at the time, the choristers were unfamiliar with the art of staging (some pre-war productions, notably The Master-Singers, were caricatured, in particular in the last act of the Festwiesee). Motley, badly organized within the scenic space on which they had to play, the coloured aspect risk was inevitable.

With Wieland, the choristers were dressed in a uniform way, reinforcing the austere character of the Brotherhood of the Grail Knights and making more uniform the two groups of flower-girls who evolved under his direction in a lascivious movement evoking the call of a maritime wave, much more evocative than an army of innkeepers of Bavarian taverns wigged and made-up to the extreme (Wagner had also regretted, after receiving the costumes of the production in 1882, the too bright and vulgar colors of the temptresses of the Garden of Klingsor). Similarly for the costumes of the soloists, sober and harmonized according to the linear and global approach wished by Wieland. The postures that were agreed upon and the gestures expected of them were disregarded; at any pose or caricatural movement, Wieland saw in the gestures of the performers the psychological reflection of their soul. A quasi-psychoanalytic approach.

The production of the Master-Singers in 1956 was proof of this: no more alleys characteristic of a cardboard postcard of medieval Nuremberg, nore colorful parades of the guilds on the banks of the Pegnitz.

The production of the Master-Singers in 1956 was proof of this: no more alleys characteristic of a cardboard postcard of medieval Nuremberg, nore colorful parades of the guilds on the banks of the Pegnitz.

Only straight light projections on minimalist decorative features (a tree, a roof, a church steeple) that invited the spectator to project themselves in the setting they wished to imagine thus avoiding any compromise with any fanatic ideology.

The same applies to Tristan (the mythical production of 1952, then the more abstract one of 1962) or to Lohengrin (1958) and Tannhäuser (1954, and especially 1961) – sometimes referred to as “oratorios” since sobriety was in order -, a set of productions coherent in the justification of their destitution and with which Wieland Wagner had succeeded his bet: finally give another dimension to a resurgent Germany which could henceforth and again proudly assert its culture and its new face.

If Wolfgang Wagner, Wieland’s brother and his collaborator in this vast undertaking of a “new Wagner” in a “New Bayreuth“, was more moderate in his approach, with for instance a more colorful aesthetic (that would be in order until the end of the 90s on the Festival stage), the npw open voice of dematerialization by the two brothers would not tolerate any step backwards. And always, with as ulterior motive the idea that Richard Wagner’s art could not deliberately suffer any more political and/or ideological confusion.

NC/SB

List of reference materials consulted for the realization of Section IV : BAYREUTH

![]()

If you wish to share further information about this article, please feel free to contact us !