If Wagner was the cultural and musical chronicler of his time, if he remained a revolutionary activist, he had also gone into the act of police, and if he was finally his master of Bayreuth celebrated as the one of the major artist of his At the time, the illustrious composer did not live before a man made of chair and blood, animated by passions, with a sometimes violent, sometimes facetious, and sometimes tender character.

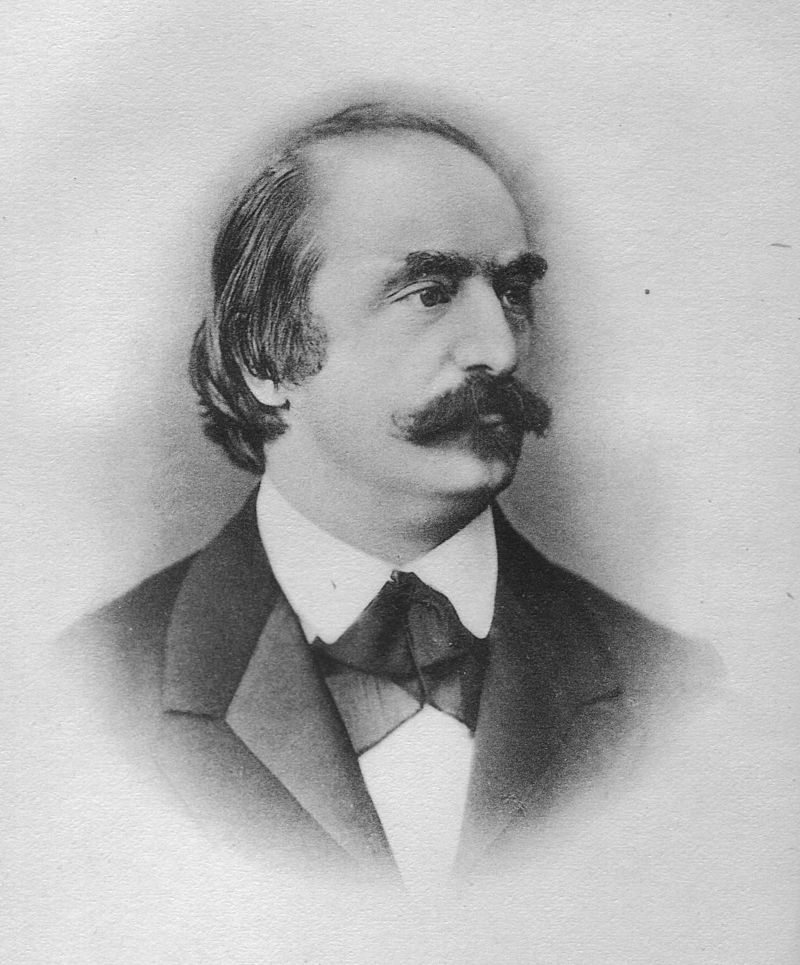

HANSLICK Eduard

(born on 11 September, 1825 – died on 6 August, 1904)

Music critic

Even though Eduard Hanslick is nowadays regarded as one of the founders of modern musical criticism, he owes his fame above all to the relentlessness he deployed against Richard Wagner for many years. A sworn enemy of the composer and perhaps the most virulent, he openly contested the value of Wagner’s music and his artistic ambitions that he considered quite pompous and even megalomaniac!

A music and law student, Eduard Hanslick was just twenty-years-old when he met Wagner, in 1845, in Marienbad; a meeting that took place under favourable auspices because the young man was then totally committed to the Wagnerian cause. Faced with the enthusiasm he expressed through torrents of inflamed missives for the composer, he invited the young Hanslick to attend the production of his latest opera, Tannhäuser, in Dresden on 19 October, 1845.

At the end of the performance, the future critic Hanslick was still under his spell, and in a first article, praised – almost with an eulogistic emphasis – the genius that was Wagner.

But quickly cracks appeared.

When Wagner – in exile in Zurich – published The Artwork of the Future in 1849, then Opera and Drama in 1851, Hanslick – who had already expressed hostility during the creation of Lohengrin in Vienna – responded almost as a sign of provocation if not of protest by a work, from his own pen this time, entitled The Beautiful in Music (Vom Musikalisch-Schönen), which came out in 1854. The work in seven chapters claimed to be in turn an attempt to reform modern music of the mid-XIXth century.

However, his knowledge of music was, according to his entourage, “deplorable” (at least it was considered this way by his contemporaries) and his pianism “more than awkward”. His targets? Wagner, first, of course, whose music he considered too descriptive and dramatic. And Liszt, of course, that he placed on an equal footing with Wagner in the pantheon of “false idols”. But the list of composers in his line of sight was long, starting with… Bach himself! About whom Hanslick declared – not without conceitedness – the purely “formal” nature of his compositions; Beethoven, afterwards, whose “incongruities” of the last works could only fall under the composer’s weakness! And so many others…

A fervent supporter of a much more conventional and classical music than what he described in his manifesto (Mozart, the first Beethoven…), Hanslick “officially” became Wagner’s sworn enemy starting from the creation of Tristan and Isolde (1865). But the critic (then appointed Professor of Music History at the prestigious University of Vienna) was more dangerous than the young student met in Dresden twenty years earlier. Recognised both in academic and artistic Viennese scenes, Hanslick became a key figure in the musical world of this second half of the XIXth century. And Wagner, against whom he fought so hard to dismantle the work in the eyes of the public, affirmed – with the tact he was known for – that the critic’s Jewish origins explained his inability to understand his work.

It was incidentally reported that the caricatural character of Beckmesser in The Master-Singers was directly inspired by Hanslick.

Proud of his editorial skills and responsibilities, Hanslick did not resist the temptation to make the trip to Bayreuth in order to attend the production of The Ring in August 1876. In a four-part critique he published in the Neue Freie Presse (“New Free Press”), Hanslick wrote a detailed report (and as one can imagine, a very acerbic one) of all the Wagnerian festivities that were then taking place on the Hill: he described the building of the Festspielhaus itself, the composition of the public whose devotion to the Master of the house he openly criticized, the performance conditions of works on stage (with irony on scenic fails), but also, of course, music and libretto of the composer which were not spared, not by a long shot.

If his second trip to Bayreuth on the occasion of Parsifal‘s performances in 1882 showed him less virulent towards Wagner’s work, it was the man – whose antisemitic “gaffes” he never forgave – he from then on lashed out at. And it did not matter if the orchestra direction – for the creation of Wagner’s most religious opera – was entrusted by the composer’s own will to a Jew, Hermann Levi! Hanslick in new publications warned the musical and artistic world of the “danger” that Wagner alone represented.

When he finished with Wagner, Eduard Hanslick went at – with almost as much energy – the work and destinies of Tchaikowsky, Richard Strauss or later Anton Bruckner, of whom he was, once again, one of the most virulent detractors. A friend of Brahms on the other hand, the critic always compared Wagner’s art with the Hungarian composer’s, in all probability creating the false idea of a rivalry between the two composers.

For if strong words, told by various close friends of Wahnfried’s circle in Bayreuth, were thrown by Wagner towards Brahms’s music, he never seemed to have persisted in destroying the work of his contemporary and fellow in an essay that would have been specially dedicated to him. Lack of time? Of interest? Or simply because only Hanslick was operating behind the scenes between the two men to accentuate this rivalry… with perhaps the secret goal of better getting people to talk about him! No one will ever know…

After Wagner’s death, and despite a very fragile health and a disease that could have assuaged his aggressiveness against his artistic enemies, it was Bruckner that the critic laid into, leading towards him a struggle, once again, without mercy.

At the end of his life, Hanslick took up the literary quill he had abandoned after having published The Beautiful in Music (Vom Musikalisch-Schönen) in 1854. From the 1870s, and for some fifteen years, he devoted himself to the writing of literary works as varied as a theoretical essay on modern opera or… the story of memories about social events he attended.

Eduard Hanslick died in Baden in 1904, after a passionate life… and an indefatigable will to sap the success of his enemies. But would Wagner have been Wagner if there had not been Hanslicks to stand in his way?

If you wish to share further information about this article, please feel free to contact us !