Wagner, the first European composer! If the name of the composer sounds more German than the noun “Germany”, the artist, himself always in search of notoriety and success that he could not find within the borders of the German Empire, exiled in his younger years to find recognition… elsewhere. And these new horizons, Wagner would seek them from London to Saint Petersburg, passing by Paris, Venice or Zurich, places that were as much living places as places of musical creation and artistic inspiration.

Venice

Wagner and Venice, Venice and Wagner…

The names of the most famous German composer and of the most romantic Italian city there is resonated together like an obvious fact…

Tristan‘s reminiscences with the plaintive singing of the gondoliers in the background and culminating with the death of the master on the notes of The Elegy, WWV93, some of the very last music notes composed by Wagner…

First stay (1858-1859)

After the scandal sparked by Minna at the hushed “Asyl“, home adjacent to the Villa Wesendonck in Zurich, Richard Wagner, then in full composition of Tristan, had no other choice but to leave Switzerland and move in a city… who would accept to welcome him.

August 1858: an arrest warrant issued against him in Dresden indeed prevented him from returning to Germany where he remained outlawed. It was by train that Wagner, accompanied by his friend and pupil Karl Ritter, went to the Grand Canal through Geneva. On 29 August, he stayed at the Hotel Danieli before taking up residence in the Palazzo Giustinian Brandolini of Adda where he would be the only tenant the next day.

August 1858: an arrest warrant issued against him in Dresden indeed prevented him from returning to Germany where he remained outlawed. It was by train that Wagner, accompanied by his friend and pupil Karl Ritter, went to the Grand Canal through Geneva. On 29 August, he stayed at the Hotel Danieli before taking up residence in the Palazzo Giustinian Brandolini of Adda where he would be the only tenant the next day.

On his arrival in Venice, Wagner devoted himself to the composition of his Tristan: Tristan-Venice, could the composer find better correspondence elsewhere?

On 3 September, the composer noted in his Diary to Mathilde: “Here (in Venice) Tristan will be finished – despite all the torments of the world. And with him, if I am allowed, I will come back to see you, to console you, to make you happy.”

Strongly imbued by the singular – even morbid – atmosphere released by the Most Serene city, Wagner was sensitive to the plaintive singing of the gondoliers that later on inspired him the melody of the shepherd in the third act of Tristan.

Strongly imbued by the singular – even morbid – atmosphere released by the Most Serene city, Wagner was sensitive to the plaintive singing of the gondoliers that later on inspired him the melody of the shepherd in the third act of Tristan.

In the Italian city whose “climate and air are divine“, surrounded by calm, Wagner finished composing Act II of Tristan. He worked hard every day with strong discipline which he imposed on himself as if he wanted to expiate a fault. Thus he reported to Minna: “I work all day until four (…) Then I cross the canal, go to St. Mark’s Square where, around five, I find Karl (Ritter) at the restaurant. After the meal, we go to the public garden in a gondola.”(Letter to Minna, 28 September, 1858).

Wagner was just as fond of ice cream at the Lavena café as the two great lions of the Arsenal whom he nicknamed Fasolt and Fafner, a nod to the two giants in The Ring.

The winter of 1858 was marked by hard work devoted to the second act of Tristan, of which Wagner drafted the orchestration at the beginning of March 1859. At the same time, he went further into his reading of Schopenhauer and multiplied the steps towards his rehabilitation in Germany, all again against a background of financial problems that overwhelmed the composer.

Yet, the Italian city, then under Austrian domination, was in danger of falling into the hands of Garibaldi’s troops. The police forces viewed in an unfavourable light the one who, besides being outlawed from Germany for his past as an anarchist agitator on the barricades of Dresden, accumulated debt. Despite his efforts, Wagner received a categorical refusal, of which he was informed by a letter received on 10 March, 1859 from von Lüttichau: no, an armistice was out of the question, much less was it welcome in Germany! End of the talks.

And at the end of March 1859, the composer was kindly asked to leave Venice. And Wagner complied on 29 March with, in his notebooks, a second act of Tristan largely orchestrated as well as drafts for Act III.

Despite his promises, it won’t be in Venice that Tristan would be finished.

Different stays: 1861 and 1876

If Wagner left Venice with the ambition to conquer the capital of culture, which was Paris, with his Tannhäuser, he went back to the Serenissima aggrieved and furious after the resounding failure of his work on the Parisian scene.

It was at the invitation of Otto and Mathilde Wesendonck that Wagner again went to Venice. But Tristan was finished before this return, before the promises made by the Grand Duke of Baden to have the work performed on the stage of the great theatre of Karlsruhe. Aborted attempt. “The Tristan affair drags on.” And with good reason: finding singers capable of surviving the production of such a musical adventure proved to be quite daunting.

It was at the invitation of Otto and Mathilde Wesendonck that Wagner again went to Venice. But Tristan was finished before this return, before the promises made by the Grand Duke of Baden to have the work performed on the stage of the great theatre of Karlsruhe. Aborted attempt. “The Tristan affair drags on.” And with good reason: finding singers capable of surviving the production of such a musical adventure proved to be quite daunting.

Between the failure of Tannhäuser and the “Tristan affair“, which did not find singers capable of producing the work, Wagner was peeved. The composer, who politely refused the offer from the Wesendoncks – that Wagner noted finding “in perfect harmony” – to share their private apartments (once bitten, twice shy!) and stayed at Hotel Danieli, only found comfort in the gallery of the Academy, when he raised his head with admiration on the painting by Titian that would undoubtedly be at the root of his inspiration for The Master-Singers of Nuremberg, or on the famous Assumption (1516), exposed today above the high altar of the Basilica dei Frari. On 11 November, 1861, Wagner decided to leave Venice. Other adventures, including the promise of having Tristan staged at the Vienna Opera, called for him.

Almost fifteen years passed without Wagner having seen the majestic spectacle of the Grand Canal again. Indeed, it was not until 1876 that the composer set foot on the quays of the Serenissima. And during these fifteen years, so many adventures filled the heart and the life of Richard Wagner: his encounter with his protector King Ludwig II of Bavaria, his love affair with Cosima, his friend Franz Liszt’s daughter, the construction of the Bayreuth Festival Theatre, the majestic setting that hosted its first edition in the summer of 1876.

Almost fifteen years passed without Wagner having seen the majestic spectacle of the Grand Canal again. Indeed, it was not until 1876 that the composer set foot on the quays of the Serenissima. And during these fifteen years, so many adventures filled the heart and the life of Richard Wagner: his encounter with his protector King Ludwig II of Bavaria, his love affair with Cosima, his friend Franz Liszt’s daughter, the construction of the Bayreuth Festival Theatre, the majestic setting that hosted its first edition in the summer of 1876.

Fifteen years that were incredibly eventful, fertile in terms of works and projects, from which Wagner came out exhausted: the composer’s health, who threw himself body and soul into having his total work of art performed on stage, has greatly degraded. Not to mention the incessant and demanding financial issues: the first Bayreuth Festival of 1876 indeed ended on the bitter note of a large deficit, which could compromise the future editions that, already, even before the first one, Wagner had in mind.

Nothing better then than a trip to Italy in the winter of 1876-77 to escape the severity of German winters. And, in order to reach Sorrento where the composer wanted to spend more than a month with his wife Cosima, a short stay in Venice, from 19 to 26 September, 1876. The couple stayed for a week at the Hotel de l’Europe. This was where the composer received the first count of the festival. Did the ghost of a lack of funds remind him of his organized flight in 1859 when he was just a meager composer among many others, in this same Serenissima? The couple soon left this decidedly hostile land. Their journey then took them to Bologna, Naples and finally Sorrento and the soothing sun of this province of Southern Italy did its job.

Ultimate stay (1882-1883)

On 16 September, 1882, after the second edition of the Bayreuth Festival, the composer arrived in Venice for his last trip. He was accompanied by his whole family, Cosima and the children, and rented the huge mezzanine (eighteen rooms) of the Palazzo Vendramin Calergi, a jewel of the 16th century Venetian civil architecture, for which he signed a three-year lease with the Count of Bardi.

The performances of Parsifal at the Bayreuth Festival aided in the Master gaining a notoriety that went far beyond the borders of Germany. And this time, the Festival had a positive financial balance: the profits were around 150,000 marks. Proud of this success, Wagner began writing a rhetorical work, the Sacred Scenic Festival in Bayreuth in 1882. This would be one of these last works concerning vocal interpretation and stage production.

But Richard Wagner was very weakened. It was not Tristan, as one might have thought, but Parsifal, his swan song, that got the better of him.

During the autumn and winter of 1882-83 visitors followed one another, with the impression that it was the last time they would see the Master alive.

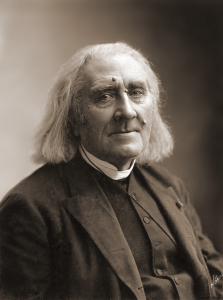

The one who was henceforth called “Abbé Liszt” was one of them. If Cosima‘s father seemed to have finally forgiven Cosima for her choices regarding her private life, the two men had strong temperaments and often lost their temper. Conversations were often turbulent to the point that Cosima, whose precautions to write down only what may seem the least controversial possible were known, even noted one of these altercations in her Diary. When Liszt visited the couple from 19 November, 1882 to 13 January, 1883, in the garden of the Vendramin Palace, the two men talked about the Music of the Future… thus undoubtedly her “future”. But Liszt measured his son-in-law’s weakness.

The one who was henceforth called “Abbé Liszt” was one of them. If Cosima‘s father seemed to have finally forgiven Cosima for her choices regarding her private life, the two men had strong temperaments and often lost their temper. Conversations were often turbulent to the point that Cosima, whose precautions to write down only what may seem the least controversial possible were known, even noted one of these altercations in her Diary. When Liszt visited the couple from 19 November, 1882 to 13 January, 1883, in the garden of the Vendramin Palace, the two men talked about the Music of the Future… thus undoubtedly her “future”. But Liszt measured his son-in-law’s weakness.

Christmas 1882 soon arrived, and Wagner offered to the La Fenice Theatre to hike up his First Symphony in Ut Major, one of his early works. Also one of his favorite. The dedication was for Cosima who was about to celebrate her forty-fifth birthday. Overwhelmed – since she did not know of the work – Cosima expressed her admiration in these terms: “the person who did this knows no fear.” A direct allusion to Siegfried from The Ring…

During the first days of 1883, Wagner learned of the invention of the phonograph: this true revolution in art, contrary to what one might think of the artist who, throughout his life, had the sole goal of trying to be known -and recognized – in all corners of the world, nevertheless deeply saddened him.

In early February 1883, the Carnival was in full swing in Venice. This was the opportunity for the Wagners, the composer and his wife, to take a walk on St. Mark’s Square where they saw the procession of the Carnival Prince. Cosima reported in her Diary that Wagner was doing quite well: the walk lasted until dawn and it was already Ash Wednesday.

The composer’s last readings were dedicated to the essay by August Bebel (Women Under Socialism) whose ideas were in line with his own preoccupations (equality between men and women and, more generally, the suppression of the masculine and the feminine, and of marriages of convenience). On this same theme, Richard Wagner began an essay with the provisional title Women in humankind (one can also offer another translation of the title, which will widen its field of action: On the feminine in the human being).

The feminine element did not leave Wagner in his final days. For there was little time left to live for the Master of Bayreuth. Wagner indeed would have received in Venice a telegram from Carrie Pringle, one of the flower-girls from Parsifal he would have loved in Bayreuth. A shock for Cosima – if one attests what was only a rumor – who would have had a go at her husband. This dispute between the two spouses was perhaps the origin of the composer’s death, Dr. Keppler, the family doctor, declaring later in his report on the death of the composer that a psychological excitement could have rushed his passing.

The feminine element did not leave Wagner in his final days. For there was little time left to live for the Master of Bayreuth. Wagner indeed would have received in Venice a telegram from Carrie Pringle, one of the flower-girls from Parsifal he would have loved in Bayreuth. A shock for Cosima – if one attests what was only a rumor – who would have had a go at her husband. This dispute between the two spouses was perhaps the origin of the composer’s death, Dr. Keppler, the family doctor, declaring later in his report on the death of the composer that a psychological excitement could have rushed his passing.

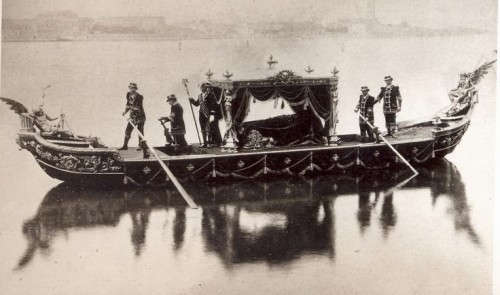

Nevertheless, on this Tuesday 13 February, 1883, Wagner met his fate.

At noon, the composer implied that the family could have lunch without him. While the rest of the family had lunch, the composer rang his maid in order for her to call his wife and the doctor. Cosima rushed and found him collapsed, incapable of articulating a word. He was laid on a sofa: Richard Wagner was already dead. It was 3:30 pm.

To follow Wagner in his footsteps in Venice:

It is Venice as a whole that should be included in your walks since Wagner loved strolling in the narrow streets of the Serenissima so much.

It is the Grand Canal – the traditional arrival of visitors in Venice – that will be the first stage of your journey. With a vaporetto, of course; it is the tradition ! For even though Wagner landed in Venice for the first time at the train station, it was the spectacle of the facades of Palaces of impudent beauty along the Grand Canal that rejoiced the composer in each of his Venetian stays. A detour to Saint Mark’s Square is then essential, as is the tasting of ice cream at Caffè Florian or at Caffè Lavena nearby, two places where Wagner himself had his own habits.

If nothing remains of the composer’s passage to the Palazzo Giustiniani, today inhabited by a known art historian and academician, a beautiful space is made to the memory of Wagner at the Palazzo Vendramin which, despite its new functions (it is indeed today one of Venice’s casinos where slot machines and other gambling games on the Internet abounds), maintains, as much as it can, the passage of its illustrious host. At the entrance of the Palace, a commemorative plaque warns the visitor that it was within these walls that the composer died.

Inside the casino, a discreet door, on the right, indicates the entrance of the Richard Wagner Museum, which is also the headquarter of the Richard Wagner Venice Association of Venice, founded in 1992 by the critic and musicologist Giuseppe Pugliese.

Inside the casino, a discreet door, on the right, indicates the entrance of the Richard Wagner Museum, which is also the headquarter of the Richard Wagner Venice Association of Venice, founded in 1992 by the critic and musicologist Giuseppe Pugliese.

A must for any Wagnerian. It only has at its disposal four of the eighteen rooms previously occupied by the Master and his family. One of them, the jewel of the Museum, is obviously the composer’s death chamber, in which he took his last breath. The sofa on which Wagner died is just a copy, the original being preserved in the Museum of the Villa Wahnfried in Bayreuth.

In the showcases of the Museum, a number of books, scores, facsimiles, lithographs, records, programs and autograph letters: the collection significantly expanded thanks to the donation of the Josef Lienhart collection in 2003.

NC.

Sources :

– article de Marie-Aude Roux : Avec le fantôme de Wagner dans Venise l’obscure (Le Monde culture, article du 13 février 2013) ;

– Cosima Wagner, Journal (Gallimard) ;

– Martin Gregor-Dellin, Richard Wagner au jour le jour (Gallimard, collection Idées)

If you wish to share further information about this article, please feel free to contact us !